pied midden : issue no. 36 : home planets : stella maria baer

Gila Rock Moons, I & II, by Stella Maria Baer, with daughter Winona. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

home again, west side

I’m back home on the western side of “the Cookie,” as my partner and I refer to this sprawling continent. It’s been a couple weeks now, and still I’m a little dazed by how wonderfully well things went setting up the exhibition series — the group Wild Pigment Project exhibition and my solo show, Records of Being Held — at form & concept gallery in O’gah’poh geh Owingeh (White Shell Water Place — also known as Santa Fe, NM). The group show was, I think it’s fair to say, immensely complicated to install, and could not have been accomplished without the heroic patience and experienced eyes and hands of Director Jordan Eddy and Operations Director Brad Hart. I really adored the entire f & c crew — including Tiana Japp, Isabella Beroutsos, Delaney Hoffman, and Marissa Fassano (who’s recently moved to another job but who played a big role in these shows) — and felt lucky to be around them every day for the three weeks it took to do the install. A totally brilliant group of people! I’m immensely grateful to gallery owner Sandy Zane for drawing them all together and for creating the space that is form & concept.

The shows are up for a whole ‘nother month, until Dec. 3rd. Next week, the online Exhibition Guide, with all the bios and other text that accompanies the work, will be up on the gallery’s website. Lots to explore there so do check it out! Also, now available: the recording of the October 11 online event, Pigments as Catalysts for Action, Decolonization & Healing : A Story-Sharing Event. Twelve of the 28 participating WPP artists share stories at this event, and I do a walkthrough of both shows, dressed in the Field Clothes jumpsuit, dyed, woven, designed and tailored for me by my partner, textile artist Noelle Guetti. This event is, I think, momentous: it really gives a multi-faceted picture of what it’s like to work as a practiced pigment practitioner today.

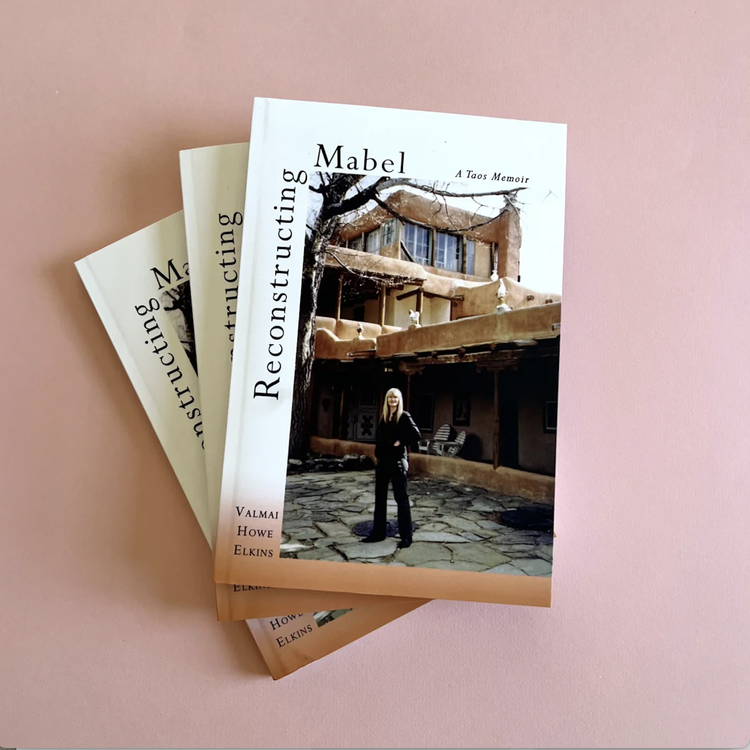

My mama’s book! Reconstructing Mabel by Valmai Howe Elkins. Image courtesy of form & concept.

My parents are writers, as I mention here from time to time. And check it out: my mother, Valmai Howe Elkins, is going to give a reading from her latest book, Reconstructing Mabel, at form & concept gallery on November 11th at 3:30, in connection with my show. The book combines vivid memoire of the years my mother spent in Taos in the 1990s, juxtaposed with accounts of Mabel Dodge Luhan, the patron of the arts associated with the Taos art colony. The reading will be part of a conversation with local film maker Mark Gordon, who will show clips from his new film, Man of Many Colors, about Blue Spruce Standing Deer(Pba’quen’nee’ee), a Tiwa artist and musician, and great-grandson of Mabel’s husband Tony Luhan, ‘as he navigates expressions of contemporary Indigeneity in an increasingly hybridized world.’ The reading/showing will be followed by a conversation addressing colonial occupation and land use. Wish I could be there! Here are more deets.

Earth pigment palette at Moon Horse Ranch. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

moon horse ranch

Much to my delight, last month, the installing of the shows coincided with the making of a new friend. In a pleasing synchronicity, pigment artist Stella Maria Baer, whose works Gila Rock Moon, I & II (the “mother and child moons”) feature in the exhibition, was also the Ground Bright pigment contributor for October. I visited Stella and her family — partner Seth and three kids, Wyeth, Whitman and Winona — at Moon Horse Ranch, which they share with an Appaloosa horse and two goats.

Artist Stella Maria Baer’s work and life, as I first beheld it on Instagram several years ago, instantly seduced me with a beauty that travelled with tender continuity from dawn-dusk shots of deserts skies and mountains, to round, planetary canvases dimensional with layers of paints made from desert dusts, to the family scenes of her kids dressed in earthy crepuscular hues.

Earth and mineral pigments in the studio. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

I’m transfixed by the harmony that Stella conjures in the spaces she creates, both inside and outside the picture frame. Her deceptively simple paintings are intricately built with textured grounds and pools of pigment that give a cosmic depth. And so much in her world — from the moon-and-stars watermelon, the white pumpkins and white globe dried flowers in her kitchen garden to the stack of earth-toned baby clothes on her night stand — resonates with her palette and textural vocabulary.

At Moon Horse ranch, Stella and I crouched in a dry wash among the junipers to talk, sifting sand between our fingers, and getting to know each other, an in-person pleasure that’s rare for me these days. I didn’t record or take notes because I wanted to be present for the flow of our conversation, but I’ve evoked some of its spirit here in our typed interview, I think. I sent Stella all the questions at once, so it’s not a back-and-forth sort of interview, but it does contain many seeds of our afternoon together. Thank you, Stella, for indulging these extensive questions with your satisfying, in-depth answers.

interview with stella maria baer

WPP: I read somewhere that you attended Divinity School (Yale?) before you discovered your path as a visual artist, when you realized that images could convey something unattainable through language. Can you say more about this revelation, and how it led you to become a painter?

SMB: Graduate school was where I realized I wanted to be a painter, but looking back the seeds were planted in childhood, and took a while to take root and bear fruit within me. Growing up my mother was a weaver and my father owned an art gallery. My grandmother was a sculptor and my grandfather was a photographer. But I never thought of art as something I wanted to do until after college. For many years my painting was a private prayer practice, an embodied meditation, something I showed to almost no one.

I studied Philosophy and Religion in college but was interested in how questions of meaning and the cosmos played out in the world. After working as a dishwasher and wrangler at my mother’s family’s ranch in Wyoming, a barista, and a summer camp counselor, I decided I wanted to study the role of art in healing and trauma, and pursued a Religion and Art degree at Yale Divinity School. At that point I had been drawing and painting birds and animals for about five years but was only showing them to my family and a few friends. While I was in graduate school I took studio classes in drawing, oil painting, and iconography and learned more about the role of art in ritual, prayer, mysticism, and post war conflict. I learned about the materiality of the spiritual. During those years I also worked as a studio assistant for artist Titus Kaphar, researching the history behind his paintings and sculptures, learning how art can recreate history and tip the scales of justice. Titus cast a vision for me for what it meant to be a working artist, to listen to dreams. He gave me critiques on my paintings and answered questions I had about techniques, materials, and color. Titus taught me to listen to my paintings and to look at my work as something sacred.

Making Appaloosa in the Painted Hills, 2019, Earth and Mineral Pigments on linen. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

Over time my studio practice eclipsed my academic work. In the drawing and painting classes I learned a language I’d been trying to speak for a long time but hadn’t known how. In one class the professor assigned a hundred paintings a week. In those classes and in the critiques with Titus my painting moved from being something private to out in the open. I learned techniques and skills I still use today. At some point during those years I realized I wanted to be a painter. For my graduate thesis I made a show of paintings hung from trees in a garden. People started telling me the paintings were speaking to them, saying things I had never dreamed they could say. Then people started asking me if they could buy the paintings. Eventually I stopped working as Titus’ studio assistant to work on my own painting and photography full time. That was ten years ago.

Wyeth making paint. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

WPP: You mentioned a struggle with Wyeth, your oldest child, who has declared red to be his favorite color. I loved that story, and the evolving conversation between you two around material choices. Would you mind sharing it here?

SMB: Wyeth has always loved red, even before he could speak he would choose the brightest of reds. I’ve never been particularly drawn to red, I’m not sure why. After many years of living on the east coast, longing to move back to where I grew up in New Mexico, I slowly filled my home and life and work with the colors of the rock and dirt I remembered from my childhood, the colors of the land and sky I was longing to return to. When Wyeth was little and first beginning to love the color red I took him on a pigment collecting trip to a hillside in Colorado with deep red rock and we gathered some together, made it into paint, and he used my painting rollers to paint red stripes into his watercolor notebook. For many years his love of red bled into my own work, and I made many red moons and paintings of red hills. During those years I connected with Heidi Gustafson, who sent me some red pigments from Santa Cruz, California, where I was born. We moved to New Mexico when I was four years old but something about those California fault line pigments and Wyeth’s love of red really spoke to me in those years, and I made several paintings from that deep red pigment, including Bear Blood Moon, made from California and New Mexico earth pigments.

Wyeth painting. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

I think one of the problems with creating online worlds is that so often I scroll through instagram and piece together an imaginary person from what I see. I follow many inspiring people and sometimes I make unreasonable assumptions about them based on what they share. I assume everyone’s home is beautiful and clean, no one has plastic based carpets like we do, no one has the same mildewy Home Depot tiles in their bathroom that were chosen before we moved in. We would love to replace those things with earth materials one day but don’t have the time or budget for it right now. But my point is I create an imaginary person who has it all and does it all from all the different people I follow and things I see. Of course if I really think about it I know that’s not true. But if I’m not careful it can seem like everyone is always on vacation in Greece or Iceland except for me. So how can I blame others when they look at my online life and assume things?

I’ve struggled with perfectionism all my life and always found it very crippling, and that I’m better off when I let go of anything being perfect. For me instagram is a living collage, its own art medium, a place I weave together many different parts of my life in one place. A place I connect with a whole cast of characters all over the world. A place people from all over the world can see my paintings and some of the things that inspire my work. I know the conventional marketing wisdom is that online we should only post one sort of thing but I’ve always been interested in little windows of different parts of life, disparate practices, many different things. The sky and the dirt and my daughter’s hands. The color of pigments and sunrises and the curve of our horse’s back.

I’m not sure I would describe our home or life as minimalist. We are drawn to natural materials and objects from the landscape around us but we have a ridiculously messy garage with at least one mouse family living in there and possibly pack rats, our closets aren’t well organized, I’ve saved most of my journals since childhood and regularly debate burning them, we haven’t cleaned the floor under our table in months, and with the three children that is not a pretty sight. I feel guilty sometimes that I don’t reflect more of that on instagram. Maybe I should do a live tour of the garage just as a reality check. Often I’m too busy trying to make a living and be present to my children and train our rescue horse and honor the grief of the end of my mother’s life to perfectly reflect back all the imperfections of our life, and tend to share the moments I find inspiring, the paintings I make, the sunrises and sunsets. Sometimes people comment they can’t believe I wear white pants while I shovel manure or go camping and I respond that thrills are hard to come by, I take them where I can, usually the white pants are covered in goat or baby poop or paint by the end of the day.

Bear Blood Moon, 2020, 52 x 54” California and New Mexico dirt on cotton. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

WPP: Your childhood camping trips with your mother inform your pigment-gathering practice. Can you tell me a little more about the personal significance of the places where you gather the dirt and rock you paint with?

SMB: I first started painting moons and planets in 2014, while I was living on the east coast, and beginning to feel a pull back to where I grew up in New Mexico. Around that time my mother started losing her memory, in what we would later learn was Alzheimer’s. I wasn’t conscious of choosing to make paintings inspired by the colors I remembered from childhood, it was just something I found myself doing, and have since then tried to understand as best I can. In many ways all my work feels that way. I try to approach it with words and there are things I can say but at the end of the day the paintings are something beyond language and that’s why I feel compelled to make them. My mother used to take us camping in canyons surrounded by pink rock, and some of my favorite memories with her are of waking up in the desert, surrounded by those colors, watching the sun rise. We didn’t have a tent, and sometimes we’d wake up in the night and see stars falling above us. For the past few years I’ve collected dirt and rock along a highway to one of the campsites she’d take us to, and every time I do I feel like I’m moving in circles around my own memory, trying to recover something that’s lost, trying to find her.

WPP: You left the Santa Fe area as a young person to attend college on the East coast, but returned as an adult, largely summoned by the landscape in the Southwest and its unique palette, reminiscent of planetary surfaces like Mars. What was it like for you to feel this summons, what’s it been like for you to come back, and how has your perspective on living here as a settler colonizer changed since you left?

SMB: Growing up in Santa Fe I always longed to move to one of the coasts. We had grandparents in California and cousins and great aunts and uncles in Massachusetts and when I left for college in 1999 I didn’t think I’d ever live in New Mexico again. In college I took an American Civil Religion class and was particularly struck by the American colonial religious idea of going westward to recreate oneself, to be reborn. I realized in that class that I came from a place in the country where white people to this day move to find themselves, to flee their histories, to recreate themselves and begin new lives. And that idea is a spiritual one that can be traced to the pilgrims, who saw their move westward as not just a chance for a new life, but a rebirth in a promised land. I was deeply uncomfortable with my own ancestors movements in the veins of those ideas, and what happened to the Indigenous people who dwelled in these lands originally.

Growing up my parents were very honest with us about the genocide of Indigenous peoples and enslavement of African peoples that our country is founded upon, and often expressed frustration at how history was taught in the schools in New Mexico. To this day, there is a controversial celebration of the conquistadors taught in New Mexican schools. As a child I was taught in the classroom to celebrate Spanish conquistadors, but only learned at home how much violence was brought with those conquests. In some ways I think my desire to move away from New Mexico and to a different part of the country was to get away from that tension, to find a place someone of my ancestry belonged more fully and was less complicit.

But of course there is no escaping that tension, no escaping being honest about our complicity, wherever we are. All of the US is on Indigenous Land. The tension is just more visible in places like New Mexico where there are greater populations of Indigenous people. Wherever we are we must face that and work to tip the scales back toward justice.

Moon Horse Ranch earth pigment palette. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

Another tension I feel is that I don’t know a place as home other than New Mexico. My ancestors like many Americans are from many places, some from France, some from England, some from Scotland, some from the Northern Ukraine, Jews who were fleeing persecution searching for a better life. But perhaps from pressure to assimilate, perhaps in line with moving west to be reborn, my ties to those cultures have almost all been lost. I know that my great great grandfather was a rabbi mystic named Teddy Baer, who used to tell his fellow village people he didn’t believe in the same God they didn’t believe in. And I know my Irish ancestors carved flowers from their homeland into their wood chairs and tables. I know in the creation story in the Hebrew Bible God breathes into dust to create human beings. There are some things I resonate with, many things I feel uncomfortable claiming as my own, others I wish I could trace, others I am trying to find a way back to.

Over the years how I seek to honor the Indigenous peoples whose land I’m on has grown and changed. I’ve come to see that knowing the history and acknowledging the genocide and whose land we are on is not enough. It is a step in the process but we must return power, resources, and sovereignty to Indigenous peoples in every way we can, not just because it’s the only just thing to do, but as Jade Bengay so often points out, the future of our planet depends on it. For us that looks like supporting Indigenous artists, businesses, politicians, farmers, and organizations, making reparations, offering workshops free to BIPOC, raising money for healthcare for Indigenous women with other artists. I mention these things only because I want to cast vision for those who may be wondering what specific action they can take, not because I feel I should be applauded for doing such things because it’s truly the least any of us can do. I always want to grow more in how best to tip back the scales of justice, and know it is something I will be learning and unlearning the rest of my life.

WPP: Non-human animals played a role in your early paintings, and continue to feature prominently in your life — your family is joined by a horse and two goats. Would you like to say more about these relationships and how they nourish you and your creative practice?

SMB: Animals have always been a part of my story, since before I was born. My mother’s family owned a sheep ranch in Wyoming, and I worked there for many years as a wrangler, training horses and leading trail rides along the river and into the mountains. We always had sheep dogs growing up, my mother spun their fur into her weavings. My mother had a leopard appaloosa growing up, and I always wanted one. This past January my husband’s sister Morgan, who has been rescuing slaughter bound horses for 20 years, found a leopard appaloosa in a kill pen in Texas. She was malnourished and frightened but gentle and longed to be touched. That weekend I sold enough paintings to buy her and we brought her home. When my son Wyeth was just learning to talk he told me of a dream he had of a horse with moons on her back. Wyeth named our appaloosa Moon and Stars. My mother never had a chance to meet her, but when I’m with Moon and Stars sometimes I think I feel my mother’s joy.

The two long haired curly goats we bought just a few weeks ago from a farmer I’ve been following for years, admiring her flock. Seth and I put goats on our wedding registry eleven years ago but this is the first time in our life we’ve had a place where we could bring them home. We named them Andromeda and Cassiopeia, after the constellations, because their fleece shine like stars. The goats serve many different purposes: they are angoras, half Navajo angoras and half American angoras, and their fleece can be spun into the softest and strongest fiber. They eat up the weeds we’ve been trying to get rid of and put nutrients back in the soil. They eat down fire hazard underbrush. They can be milked. And they provide companions for our horse, who is fond of them and often grazes the wild grasses near them. For us they bring so much joy, and are a way we can give back to the land, deepen the richness of the soil, and care for and honor this place we live. The goats did eat my cosmos and the last of the globe amaranth flowers in the garden. But it seems only right that this year’s cosmos will become next year’s garden.

Stella with earth and mineral pigments in the studio. Image courtesy of Stella Maria Baer.

WPP: Finally, do you have an aspiration for the coming year that you’d like to share here?

SMB: Our vision for our home, our little ranch we call Moon Horse Ranch, is a place of deeper connection, with the land, with ourselves, with one another, not just for our family but all who come here. We experienced that this past year with the Earth Pigment Paint Making Workshops I taught in our fields. After the past few years we are all hungry for connection. Isolation and separation has left deep longings in us from which we are all trying to recover. I hope to continue to deepen those connections, with the land, with my own self, with others. Meeting you Tilke, connecting through this project with so many pigment siblings as Caroline Ross described us, wrestling with what it means to honor the land and honor the original peoples of this land, these are all questions I will wrestle with the rest of my life.

(end interview)

Group exhibition at form & concept. Image courtesy of form & concept.

have pigments, will travel?

I have an aspiration: I would really love to see the Wild Pigment Project group exhibition travel and be exhibited in other places. It’s been magic to watch people enter the gallery, and move around from piece to piece and pigment set to pigment set, utterly engrossed and looking at every single thing, reading all the text. They’ve said things like, “I feel so held in here. I just feel so grounded,” “I feel like I’ve found my people!” and, “I don’t want to leave!”

This exhibit is unique in that it gives a felt sense of the pigments themselves andthe context of their collaborations with artists. It draws so many lines that aren’t drawn when the two are separate.

If you have any thoughts about institutions or galleries that might be interested in exhibiting this show, please let me know soon (of course, they would need to be equipped to host the show and to cover all the associated costs…unless we do some collective fund raising to help out with that!).

Also, the pigment sets and gorgeous art by your favorite artists might be good gifts…for yourself or for people you love. If you’re feeling flush and you want to support these generous artists (and give to the Institute of American Indian Art at the same time — they get 22% of profits), go check out what’s still available for sale. My own work is also for sale/rent…including the leaves I clean my brushes on, which become like minimalist watercolor pans. They can come to you for just $11 each. Contact form & concept for info.

All for now — I’ve just launched into my November Being with Pigments course, and I’m utterly bowled over by the unbelievable group of artists I’ll be working with this month. I have some special things to do to prep for my sessions next week, so I’d better scuttle off.

And yes, you may have noticed that this newsletter is quite a bit later than it should be…it’s already November, you’re so right! I was, uh, busy. :)

Next newsletter — an impassioned piece of writing about the history of public forests by artist Hosanna, who’s contributing a beautiful Basalt Blue — may follow close on the heels of this one.

Please do write to me if these words (or any other aspect of this project) have inspired you — your feedback is a reward I savor. Just hit reply to this email or find me at info@wildpigmentproject.org.

Stay by the fire (for those of you in Autumn, that is!),

<3 Tilke

Moon-and-stars watermelon at Moon Horse Ranch. Photo by Tilke Elkins.