pied midden : issue no. 25 : dancing with dust : marjorie morgan & josh ruder

Walnut husks with husk fly larvae/Marjorie Morgan and husk flies. Image courtesy of Marjorie Morgan.

what’s in a midden?

A ‘midden’ is a trash heap. When I founded Wild Pigment Project in 2019, I called this newsletter ‘Pied Midden’ in part because I saw so many exciting and available wild (and pied! as in, multi-colored) pigments in trash heaps: mining slag, compost bins, construction dumps, squirrel nut-husk mounds, leaf litter (“tree trash!”). What’s exciting about a midden, really, is that it represents a chaotic accumulation, a sort of freakish concentration of similar materials that have been brought together in one place and abandoned. Left as “useless” by one being, they become a site of careless richness, a fertile place that invites new life, just as dung gives life to mushrooms. More on mushrooms in a sec.

When synthetic pigments really took hold in dominant culture, in the early 20th century, ancient European botanical and mineral pigment use began to be pushed out, deposited in history books as quaint but inadequate. As global colonizing systems have spread, the discarded or suppressed Western knowledge of foraged pigments has fermented in the trash heap of the past, along with much Indigenous pigment knowledge which was destroyed, crushed, hidden, or forced to find secret refuge. But like all things which find their way to a trash heap, buried pigment knowledge is interlaced with networks of relationships, like mycelial bodies. The memory of ancient pigment practices has thrived under the surface, waiting to bloom again.

trash legacy

This global pigment foraging movement — I believe I can call it that now, with gusto, even! — is the giant mushroom that blooms on the refuse heaps of the past, as well as on the literal refuse of the present. Artists and researchers interested in working with wild pigments often come to them in revelation, as a rebirth of sorts, as a pheonixing, as a rising out of ashes and trash. The trash of a global culture that has begun to visibly decompose, both materially and psychically. The mind-trash of lives lived out of concert with inner values, lives out of concert with the rest of planetary life.

As this movement builds momentum, I can get a little pang of fear about its consequences for wild places. The myth of the Tragedy of the Commons, which was a critical text in the early days of the budding of global capitalism, tells us that individuals are greedy. If we believe that, then the rising popularity of wild pigments among artists can only mean one thing: this new “trend” will surely result in the further ravaging of the planet, as every available pigment-yielding animal, mineral and vegetable is plucked from the earth and converted into ink, paint and dye to sell to the highest bidder. Stupid, greedy people will wreck everything, even if some of us know better.

i’m going to boldly suggest that that isn’t likely to happen, for a few reasons. One is that the people who are drawn to these pigments are overwhelmingly, as far as I can see, in it out of reverence for other species, and come to it wanting to increase their sensitivity to all life. A surprising majority of pigment people see pigments as people. And the animism of other-than-human worlds may be the only thing that’s going to make us choose each other instead of just ourselves. I’m willing to risk driving a few lost souls to destructive behaviors, if it means I can inspire a whole lot more people to fall more deeply in love with this world.

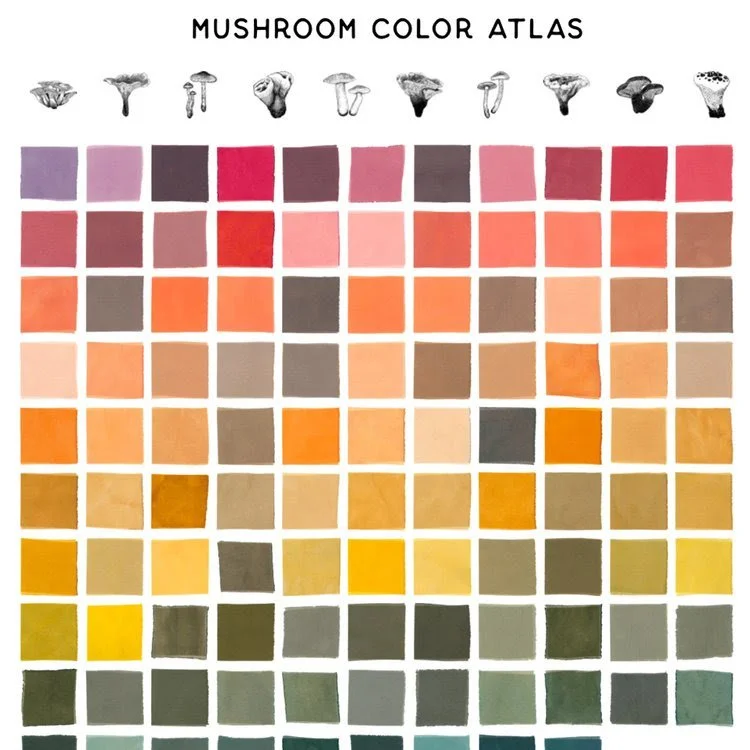

So is Julie Beeler. She just launched the incredible Mushroom Color Atlas, a total labor of love which sets my heart racing with mushroom adoration and will without a doubt inspire a multitude of artists to explore fungal pigments. Are these newbies gonna trample the wilds into a pulp and overharvest every mushroom they find? Well, no, not likely. Especially not mushrooms. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of larger mycelia which live underground, and picking the mushroom-fruit — even picking ALL of them (which you wouldn’t want to do, because it’s just rude) — doesn’t harm their population. If anything, it moves their spores around and increases mushroom numbers. It’s true that other plants can be damaged by trampling, but — I think most people take more, rather than less, care.

There are many sensitive plants, minerals and animals that should not be crushed into pigment, and I think most artist-foragers have a sense of this, and do the appropriate research. Last year, I posted the Wild Pigment Project Reciprocal Foraging Guidelines, if you’re looking for reflections on ethical foraging. When considering pigments for my creative practice, I personally favor the midden, the trash heap, the refuse pile. It’s the place where materials are ready and waiting to be broken down (ground down, boiled down) and transmuted into something else. Right now, in the north, city gutters are rolling with rotting black walnuts, and leaf piles are overflowing with a full palette of subtle colors. My kitchen compost is stuffed with onion skins, avocado pits, and cabbage peelings. The broken bricks in the alleys are returning to dust underfoot. I look there first.

midden ghosts

Descendants of colonizers feel to me like ghosts of sorts, beings severed from place. Our land lineages are short, if they exist at all, and they’re woven through with acts of theft, violence and deception. Even if I feel profound love for the places where I grew up and the beings there that raised me, as do other settler colonizer descendants, there are so many threads of relationship I can’t find and follow. The lack of an ancient connection to a specific geographical location lies on us like a grey weight, a grief-filled absence, a truth that can’t be undone. Without lineaged land bodies, our land practices have resulted in whole new kinds of middens, like the plastic trash midden “the size of Texas” that drifts across the Pacific ocean, the pools-of-mercury middens at the bottoms of the Great Lakes, and the encapsulated radioactive waste middens buried deep in the Earth’s crust. In a sense, these places of waste are the most tangible sites of my lineage, the places where perhaps, on some level, I can — or should — feel at home, because I know I owe these dangerous and potent materials many thanks for the way of life they’ve given me. Ghosts are said to find rest when the injustices committed against them are faced and made known. In this way, can I find my land lineage by facing these middens as my birthright and responsibility? My home?

Wild Ink Monotype by Marjorie Morgan. Image courtesy of Marjorie Morgan.

from dust and ashes

This month’s Ground Bright pigment contribution, SCULPTOR’S DUST is the product of a friendship between a painter/printmaker and a sculptor: Marjorie Morgan and Joshua Ruder. Their friendship activated what I’ll call a ‘dust midden’ — a reserve of pulverized marble that Josh removed from the stones he sculpted and was saving without knowing quite what he’d do with it, until he met Marjorie. When Marjorie saw the dust, she thought of Ground Bright, and suggested that the rich white pigment would make a perfect contribution. Marble dust not only makes a beautiful soft white pigment: it’s also a key component in lake-making and gesso, and can also be used as a substrate for painting. Marjorie has explored its many uses, and was excited to share her recipes with subscribers.

The marble was itself foraged from a refuse pile, a heap of fragments discarded at an abandoned marble quarry in Vermont, and carried out by Josh in a backpack. This dialog with tossed marble is a crucial part of Josh’s creative process. In foraging, he tunes into place, he listens for what the stones have to say about where they’ve been.

Marjorie’s path to wild pigments has a flavor of rebirth from ashes to it. An acclaimed career as a performance-based artist was burned to the ground in 2011, when a serious injury reduced her ability to dance and perform. Not long before, she’d inexplicably found her way through a door into painting, and it was this that took root in her new life and blossomed into what is now a rich career as a visual artist. Marjorie’s explorations with wild printmaking inks are especially riveting to me, since toxic synthetic printmaking inks are what first inspired me to begin exploring wild color, waaay back in the last century.

I’ve interviewed both Josh and Marjorie here. I think you’ll be excited by their lines of visual and tactile inquiry.

Wild inks monotype by Marjorie Morgan. Image courtesy of Marjorie Morgan.

interview with marjorie morgan

WPP: I love the story of how you found your way into your first significant painting after your dance injury. Would you mind briefly sharing it here?

MM: I actually started painting 2 years before my injury.

I learned how to paint rather accidentally. I was hired as a cook at an arts program in France (my wife had studied there, and then was asked back as a cook… and I joined her); and I got really inspired by the artwork that the teen students were doing. I thought, “If these kids can have the guts to do this, I can at least try.” So I started shadowing classes with the next group (art teachers) when I wasn’t cooking. The art teachers were learning how to paint plein air, so I would diligently go out and work on my painting every afternoon between 2 and 5. Every day, fewer painters were out there because they either finished, got frustrated or moved on to something else. I just kept going and going. And eventually, I was the only one still painting plein air. One afternoon, I was painting away and a group member walked by. She said, “You have quite the audience.” Surprised, I turned around and saw over a dozen goats quietly looking on. I finally finished that painting (and even sold it!) and have been creating visual art ever since.

My dance friends actually used to question the time I was putting into painting, but it sure paid off. I had easy access to a new creative outlet when I had to stop dancing so suddenly.

WPP: Are there visual parallels between the forms your body used to follow as a dancer and what shows up in your paintings? In other words, does your painting practice feel like a continuation of the visual vocabulary you developed as a dancer, or is it quite different? Feel free to illustrate this with visual examples, if that’s possible!

MM: My printmaking and painting practices feel more like a continuation of the process of making dances, not so much a continuation of any visual vocabulary. That being said, some of the works look like dance or even dancers, but in an abstract way. They have a lot of movement in them. I give credit for that to the materials themselves. The inks, in particular, love to move and flow and create their own choreography. As a dancer, I loved to choreograph, improvise and collaborate; and that is a lot of what I do with natural inks. The inks will just start to move on their own, and the work gets created by my responses to that movement. Each print or painting is like a dance between me and the inks. And the inks, like dancers, are ever changing and are created themselves from organic material.

One of my favorite ink/dance collaborations was with black walnut ink and husk fly larvae (see image at top of page). A couple of years ago, after foraging some black walnut hulls, I noticed that they were inhabited with bugs, and these bugs seemed to be leaving inky trails behind.

So I put the hulls out on my back porch on white paper and left them overnight. The next morning, I rushed out to see what was happening, and I was astounded. I saw the inky evidence of an incredible dance between bugs and hulls. I consider myself a collaborator in the piece, but my role was actually pretty small. Those larvae did most of the work!

When I work with natural pigments (as opposed to dye-based inks), the feeling is very different. The movement is much slower and I tend to create images of land masses or planets… things that are the actual sources of the pigments. That was not at all premeditated, but something that just instinctively felt right.

So working with the inks does feel like choreographing to me, and it’s quick and reactive.

Working with the pigments feels more like traditional painting…but painting with the planet itself; and it is slower and more methodical.

Oil painting with pigments on marble substrate by Marjorie Morgan. Image courtesy of Marjorie Morgan.

WPP: What clued you into working with wild pigments? How does your pigment practice (foraging and paint and ink making) speak to your current creative expression/aspiration?

MM: I started working with wild pigments when I moved out to the country and into a house that had limited spaces for me to clean my paint brushes. It felt like madness to be having toxic materials in my kitchen, so I started experimenting with natural ways of finding color.

I have always been an artist who likes to experiment and solve problems, and working with wild colors gives me constant questions to answer. I also love connecting to our natural world, and this practice has pulled together my love for nature and my love for art. I am so happy when I’m outdoors, foraging for materials. And even when I am back indoors in my studio, the inks have brought the outside world in with them.

I aspire to find flow and authenticity as an artist. I can’t imagine better teachers for this than natural inks. Our planet has so much to teach us about creativity, and I am a willing and eager student.

WPP: Like me, when you first went deep into pigment exploration, you stopped using synthetic pigments completely. Recently, you’ve begun to reincorporate some synthetic pigments back into your studio work. What inspired your return to synthetic pigments? How has your dialog with these synthetic colors changed? Do you have any advice for people who are wondering whether it’s ok to use both synthetic and natural pigments together?

MM: I decided to work only with natural materials until I had really figured some things out. That meant that I cleared my studio of all commercially made paints and inks, partly to just have a break from the toxicity and partly to make sure I didn’t fall back into old ways of working.

That period of time ended up being almost exactly two years.

And now I am gently reintroducing commercially made oil paints, acrylics, gouache and Akua intaglio inks.

And I’m not sure exactly why, but I think some of it is because (as I mentioned before) I love to solve problems as an artist. So my new problem set is: how, why and when to work with which materials? And what kinds of images do these materials want to create in collaboration with me?

I have no idea where these questions will take me.

But I can say that I already feel that acrylic paints just don’t excite me anymore (or at least right now). They feel so “dead” compared to natural inks and paints. I’ll push them, for sure, and I’ll try combining them with natural materials to see what happens. But that already was both surprising and completely predictable.

I believe in breaking “the rules” artistically. So I think you can do whatever you want as long as you are not damaging yourself or others. The question then arises… how damaging are commercially made materials to oneself, others and the planet? Can the creative energy released in making work somehow offset the toxicity of the materials? So, I clearly have more questions than answers when it comes to materials, and that is why I am in this new phase of experimentation.

Marjorie’s monotype technique. Image courtesy of Marjorie Morgan.

WPP: You’ve figured out some valuable ways of working with wild pigments as printmaking inks. Would you mind sharing a bit about those here? (pics would be good for this too).

MM: I just got into a conversation about natural materials... and how some of us White folks are claiming to have “discovered” methods that have probably been in use for a very long time, to be "pioneers" of this and that technique. And it made me think of this word, “pioneer,” and how it is such a part of colonialism and White supremacy culture.

So I don’t really think I have discovered anything at all.

After lots of trial and error, I came up with a consistently successful way of creating monotypes with natural inks. You apply the inks directly to a plate (I use petg plates), let the inks dry out completely, and then print the plate on dampened paper. The moisture rehydrates the inks instantly, and the inks move right into the paper and hold their form. It’s fairly simple, but feels magical.

I’ve also created inks for silkscreening with natural inks, and have a variety of recipes for earth pigment inks that work with woodcuts, monotypes, monoprints and even drypoint.

WPP: How did you meet Josh, and how did this collaboration come about?

MM: I met Josh at a critique group that he hosts in Greenfield, MA.

I was just starting to create large-scale natural ink monotypes, and it was fun (and scary) to put them forward to strangers and get feedback.

In addition to hosting, Josh also shared his own beautiful creations of rock, wood and marble.

I had previously created a body of work of oil paintings on marble substrate, but was wanting to use only natural, handmade materials, so I had put that work away.

And then it occurred to me that Josh probably had a lot of marble dust from his sculpting process. So I asked, and was presented with a large container of marble dust several months later.

And it worked! So I now have a friendship with Josh and his marble dust!

Image courtesy of Sydney Matrisciano.

interview with josh ruder (the long version!)

WPP: Can you describe how the collaborative contribution with Marjorie, of Sculptor’s Dust to Ground Bright came to be? Were you surprised when she asked if she could have some of your marble dust?

JR: I think that Marjorie did a great job describing how this collaboration began. When she asked me if I had marble dust that she could use for her art practice, I had just added a new dust collector to my studio which has been essential in protecting my lungs from dust that is created when I cut, grind, and carve stone and also allows me to easily collect the fine dust that I create and be able to bag it up and give to Marjorie. It is so exciting for this material to be reused to create art instead of being thrown away.

WPP: You also forage for your materials. Can you describe how the physicality of this process, and the connection to the land that comes with it, is central to your creative practice?

JR: I find so much beauty in the found stones that I use to create my sculptures. I can see the hints of their incredible potential once carved, polished, and placed in the right orientation. I do not see sculptures within most regular blocks of marble that can be bought from quarries, and I love the process of exploring and hunting in the scrap piles for the perfect stones that speak to me and beg to be hiked out and turned into a sculpture. The limitations of the stones that I find are what I love most about them. They are the challenges and gifts that the stones present and are what make each of my sculptures unique beings.

Nature is truly the greatest sculptor. I always find the best stones when I am out in nature being completely open to the endless forms around me. Certain lines, textures, shadows, and volumes seem to jump out at me from the landscape and call me to investigate. The marble that I find is a collaboration between the natural forces that created it and the human forces that violently removed it from the ground. I feel that the care and love that I give to each of the marble fragments that I carve can be a tiny step in healing our connection with nature. I think that I am always seeking to find and communicate the harmony between humanity and the world that is our home and provides everything for us.

Image courtesy of Joshua Ruder.

WPP: I think readers would enjoy a quick description of how marble goes from a solid, two-million-year-old metamorphic part of the landscape to a finely-ground white dust. How do you do it??

JR: I have many ways that I transform the marble from the raw stone that I find into a finished sculpture, and all of them create chips and dust. The main process that creates the fine dust that I am sharing with you is a grinder with a diamond blade on it that I use to cut and grind the marble. I also use an air hammer and chisels to do much of the shaping of the marble. I finish by filing and sanding the surface until it is completely smooth and free of scratches and evidence of my work.

WPP: Is it true that marble’s not vegan, because it’s made up of the calciferous shells of ancient marine creatures? I read that, and it’s fun to say, but is all calcite the product of a creature?

JR: This is an interesting question that I do not have a definite answer to. I have had some very interesting conversations about this question and look forward to digging deeper. At the moment, I am leaning towards thinking that marble is vegan. It is true that the main component of marble is the shells and skeletons of ancient marine creatures. However, they were not the casualties of humanity’s exploitative practices. They lived and died millions of years before the earliest humans walked this earth and have since undergone an incredible geologic transformation that has turned them into rock and then changed that rock’s crystal structure again to create the sparkling marble that we know. I do believe that quarrying is an incredibly destructive process that has left many scars on the landscape. This is a part of why I connect so much with my process of foraging for marble, so that I am not further participating in those exploitative processes.

(end interview)

Thanks so much, Josh and Marjorie! That was a sweet time we had together.

third collaborator

Josh and Marjorie both agreed that in a way, I played a small, third role in this collaboration. In discussing where to direct Ground Bright’s 22%, I suggested that the donation go to the Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi. The Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi is a community of extended families who has inhabited the Missisquoi River and the Betobagw (Lake Champlain) Valley for thousands of years. This land has nourished me, Marjorie and Josh in different ways, and I’m extremely grateful for this opportunity to offer some reciprocity to the land’s traditional custodians. If you read issue no. 24, you’ll have some idea of what it means to me.

Thank you for reading ~ write to me if you’re moved to. I always love hearing from you.

Stay Dusty,

<3 Tilke

Found pigments-of-place by a great northern lake. Pigments & pic by me, Tilke Elkins