pied midden : issue no. 26 : acknowledging the land : nancy pobanz

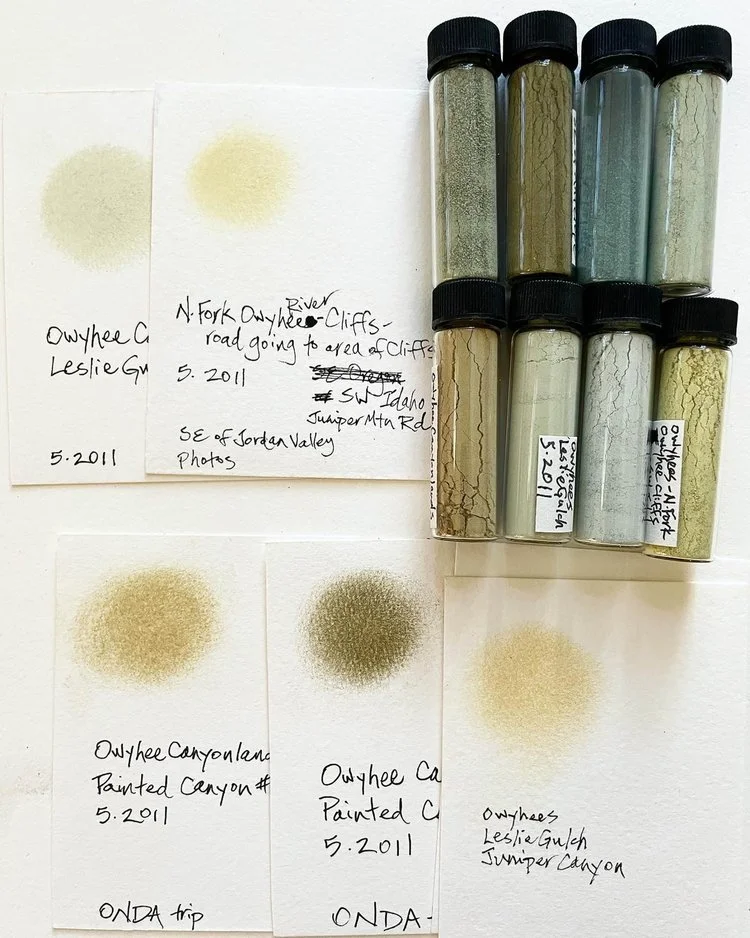

Foraged dusts, gathered by Tilke Elkins. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

As we engage in processes of reconciliation it is critical that land acknowledgements don't become a token gesture. They are not meant to be static, scripted statements that every person must recite in exactly the same way. They are expressions of relationship, acknowledging not just the territory someone is on, but that person’s connection to that land based on knowledge that has been shared with them.

Lindsay DuPré- Metis Nation, from www.whose.land/en/

my land acknowledgement

I’d like to thank all the beings and the elementals, the rivers and the forests and the mountains of this place for holding me in their rhythms. On this land where I’m a visitor, I’d like to thank the traditional custodians, the Chaffin Kalapuya people, who have been here in this valley for more than 12,000 years. I would like to thank Kalapuya elder Esther Stutzman, and Kalapuya historian Davis Lewis for sharing their knowledge of Kalapuya history. I acknowledge that the abundance of this valley is available to me as a result of the vital relationship between the the land and Kalapuyans who once managed this valley for fertility through controlled burning and who, as a result of colonization, were forcibly removed to reservations in the mid 1800s, and today are part of both the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz.

I acknowledge that the ease of my life here as a White person rests on a long history of racism in Oregon, ongoing racism towards Black and Indigenous people, Latinx people, Asian Americans, and many other populations. This racism has brought immeasurable suffering to many. Studying this history, and the history of my own ancestral lineages, most of which are English, and working to overcome racism, cultural erasure and ecocide by donating my time and money to these causes are actions I take to offer my respect and gratitude to this place.

‘be fey, do grime.’*

For those of us who orient our lives with pigments as a central compass point, the attraction to wild pigments is the beginning of our land acknowledgement. Whatever tiny receptacles we use to carry these lakes and ochres, these distillations of summer sun or rock-turned-dust — in glass vials, in old medicine bottles, cigar tubes, or plastic bags or pudding jars (my fav) — these powders are acknowledgements of an attraction to the beauty of the body of the land, recognitions of the call to touch and to hold and to be coated in minute particles of the land, to fill the valleys between the ridges in our fingerprints with microscopic boulders of pure color. This longing to be coated, to be touched as only dust can touch us, entirely and even invisibly, is so strong for many of us that we invite it against our better judgement. The dangers of this communion can be real — to invite dust into our delicate systems can be treacherous; poisonous (heavy metals and other toxic minerals can hide in so many forms of ground rock or soil: arsenic in mined earth, mercury in ocean calciums, lead and cadmium in exhaust fallout) or merely suffocating (silicosis from exposure to fine silica-rich dust particles is the top occupational hazard on the planet). And still, consider the enduring appeal of the ochre-stained hand, or the arms planted deep into the dye vat, naked of gloves. We want to touch and be touched by pigments. This touch, this physical contact is the door that opens us to whatever our encounter with the molecular magic in the atoms of the dust we touch may hold for us: the medicine of pleasure, the shadows of decline, or other mysteries that balance us beyond light and dark.

This acknowledgement of beauty, and of our longing for beauty, as well as for touch is what seeds the need to take, I think. And if we’re lucky, the need to reciprocate, to give back. To act in reciprocity, to acknowledge the gifts of the land is, I believe, ultimately, to acknowledge what the land has gone through to bring us those gifts: to ask, who belongs to the land, and who does the land belong to, where ‘belonging’ means ‘love’. Who loves the land, and who is loved by the land? The lands I love are loved by generations of people who are not my ancestors. The Kalapuya people love these lands like their greatest-grandparents loved them. How can I really know — and love? — this place without knowing who the land loves and has loved? Even if I know the land loves me, too?

How does the land love me and how do I love the land? This is a question that Robin Wall Kimmerer has asked her dumbfounded students: you know you love the land, but do you also know that the land loves you?** To acknowledge that the land loves you is also to acknowledge that the land also loves those generations of people who have been divided from the land, the Indigenous Peoples who have been stolen from the land and have had the land stolen from them.

To acknowledge the land is to acknowledge not just how the land gives, but also who the land loves, and how the land grieves. A land acknowledgement, felt and real, not proscribed and rote, is this — the acknowledging of love, where it’s felt and where it’s lost, and how griefs and gratitudes are held together in the smallest scoop of colored dust.

Ground Bright pigments, 2021. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

pre & post foraging guidelines too

Just as a living land acknowledgement isn’t a static, scripted statement or a token gesture, foraging guidelines are personal and ever-evolving. If you’re a forager, what are yours? These blueprints of reciprocity are, I think, like the words you whisper in your best friend’s ear when you have a sleep over and it gets so late that time slows down and you’re the only ones awake in the galaxy, and you both say exactly the things that are in your hearts to say. Those are the conversations passing wordlessly between you and the land as you forage, because you’re listening and the earth is listening back. Can you write them down?

I wrote the Reciprocal Foraging Guidelines for Wild Pigment Project a little over a year ago, based on inspiration from Robin Wall Kimmerer and other Honorable Harvest-like traditions from many different Indigenous Peoples. And while they’re certainly true for me, they’re broad, meant to contain a wide range of possible experience. My personal guidelines aren’t ‘rules’ as much as a description of what I actually do, most of the time. I want to share those with you now, here. What you do with what you have before you start foraging, and after you’ve foraged is, I’ve realized, just as important to the land as what you do while foraging. These are descriptions of what I actually do, most of the time — not what I think everyone should necessarily do.

MY RECIPROCAL PRE-FORAGING GUIDELINES

I use what I already have.

I use materials that feel out-of-use because they’ve been ‘stored.’

I use what other people have been storing without using.

I use what comes from the waste stream around me.

I use what’s closest to me.

I work with materials that delight me.

I don’t work with materials I don’t really love.

MY RECIPROCAL FORAGING GUIDELINES

I forage where I am and where I find myself. I don’t seek out special places to forage for particular materials.

I forage in places where I have a personal connection, or feel especially called to forage.

I practice un-foraging — leaving rocks, earth or plants that might make good pigments where they are, touching them or picking them up, admiring them, and then putting them back down where I found them (thanks Elaine Su-Hui, for reminding me of the value of this!).

I’m committed to listening to my inner voice around what I should or should not bring home with me. I listen carefully to the very first impression I have when I find something, and I follow that. If the feeling about whether I should take something or not is unclear, then I don’t.

I know exactly what I want to use the material for when i find it, and I take the smallest possible quantity home with me. If I don’t know what I might do with the material, then I leave it there, even if I really love it.

I offer thanks, in a variety of ways that feel sincere. Saying thank you, feeling gratitude deeply, picking up trash, leaving some dried herbs that I value and have brought with me to leave as gifts are a few of my ways of saying thanks.

I share some of what I take.

I look for opportunities to give back to the place where I forage, either with my time or with cash donations to land stewardship groups.

I look for opportunities to increase friendships with people connected to the land who are both like me and not like me.

I spend time learning about the land and its history. I share what I learn.

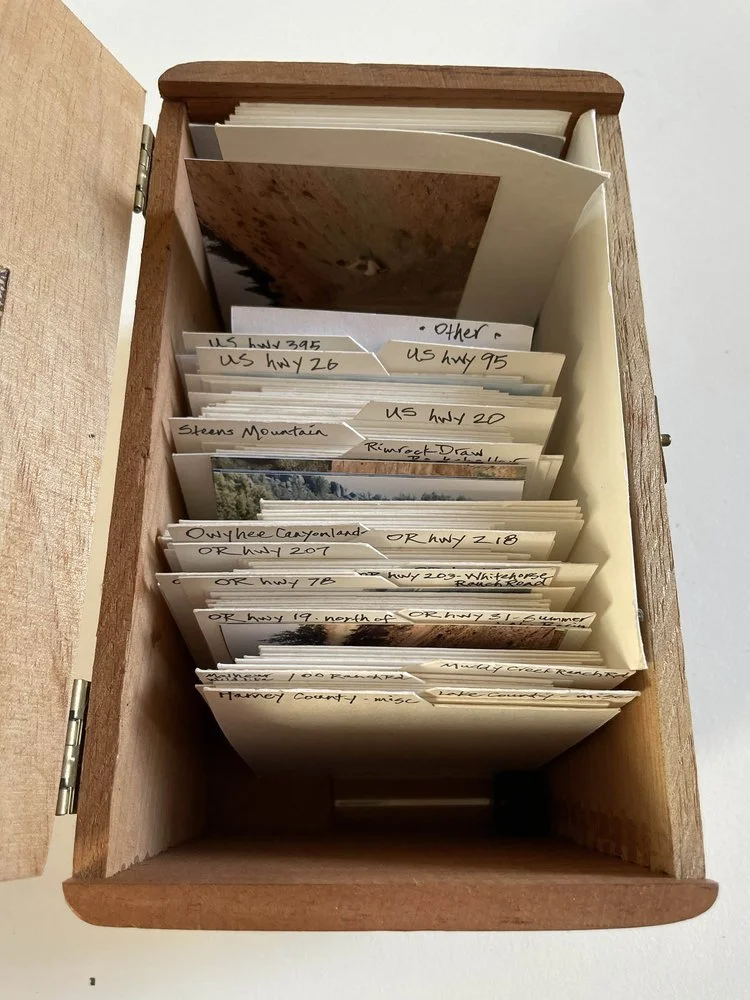

SE OREGON, Ground Bright’s December pigment, contributed by Nancy’s Pobanz. Photo by Noelle Guetti.

MY RECIPROCAL POST-FORAGING GUIDELINES

In my early days of foraging and making my own painting materials, I often watched in dismay as I accumulated more than I could use, or lost track of what exactly I had in the shadowy corners of my studio. It took a while, but eventually, I developed an urgency to change. I internalized another structure of guidelines, one that had to do with respecting materials post-foraging. There are four of them. I wish someone had told them to me back in the day.

1. REMEMBER WHAT YOU FORAGE

Have a clear way to remember exactly where you found whatever you bring home. Use memory mnemonics (‘this is the shape of a bear and it reminds me of going to that lake with my friend Bear last summer”) or write things down and keep the words near the materials.

My favorite way is to write little stories on cards and store them in the container with the material — cloth bag, glass jar, zip-lock bag, tiny vial. Do this AS SOON AS POSSIBLE.

I used to use stickers but now I don’t. I like cards because they’re easy to move and change as the pigment moves and changes.

2. USE WHAT YOU’VE GATHERED RIGHT AWAY

Make a practice of working with a material as soon as you find it, before you gather something else.

When you gather plant parts, clean and freeze, boil or dry them right away. Label the material and store it in a way that will preserve it best.

When you bring home a rock or some soil to use for pigment or paint, grind it, label it and store it right away, instead of just putting it in a pile of other rocks and earths.

3. CHOOSE STORAGE CONTAINERS YOU LIKE

Don’t underestimate the power of a container to affect your enthusiasm for working with a material. If you’re like me, then if the containers you use to store things are ugly, that may affect how you feel about what they’re storing. If you’re avoiding looking at or working with the containers, the material they hold becomes hidden from you.

If you don’t use what you gather, it’s a little bit like just taking it and throwing it in a landfill. Use is what honors material.

That said, I think it’s really important to be relaxed when working with wild pigments, not to be too precious and try and conserve every tiny little particle of dust. It’s ok to spill things, it’s ok to behave normally, to be yourself and be relaxed.

4. CLEAN UP IMMEDIATELY

As soon as you’re done working with a material, clean up your messes. Scrape up the dust, clean the glass plates and mullers, pick up the stray plant parts. Do this while you’re still in touch with the material, and while it’s easy to scrape off what you haven’t used and store it for later. If you wait, things can become hardened, faded, brittle, and dusty, and you may not want to spend the time required to make the most of what’s there or what’s left on your tools. To clean right away is to show respect to the material, to give your full presence and attention, and to say that you want to treat the material with care and intention — that’s honoring, that’s gratitude, that’s reciprocity.

* The brilliant artist/pigment practitioner Caroline Ross wrote this at the end of an Instagram post recently, to summarize a little jolt of pigment inspiration: “…art is for everyone. Earth is an artist. Don’t swallow that scarcity = value crap. Dirt is everywhere, a big massive ball of it hurtling through space is our beautiful home. Be fey, do grime.” Thanks for this exhortation, Caro!

** “Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.” — Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants.

Pigments from SE Oregon foraged and catalogued by artist Nancy Pobanz. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

Artist Nancy Pobanz has been thinking about her relationship with desert dusts for most of her life. She grew up in a town called Ontario, on the farthest-east border of the Oregon desert, helping her mom collect local clay to be used in her ceramics, and her dad bring home colored earths from a road trip. As a young person with a craving for plants and greenery, she left the desert and sought out green places. She travelled, spending time in the plant-rich Philippines before moving to Eugene, in Oregon’s lush valley between the Coast Range and the cascades.

One day in 1996 she travelled back home to the desert and felt a new affinity for the vast stretches of mineral reds, purples, greens, grey and pinks she saw there. She thought to copy them with her (then acrylic) paints, and so she gathered samples….until it struck her, why not paint with the earths themselves! That was her doorway in to reconnecting with this landscape, figuring out how to make earth paints, and deepening her connection to the desert. In 2015, she was invited to be the artist-in-residence at an important prehistoric archeological dig in Harney County, Oregon, led by Patrick O’Grady, of the UO Museum of Natural & Cultural History, at the Rimrock Draw Rockshelter on Northern Paiute lands.

Nancy lives only a few blocks from me, though we didn’t meet each other until a couple of years ago. This month, I visited her in her beautiful cozy studio in the garden behind the home she shares with her husband David, who was excited to share some of the unusual berries that were still edible, so late in the season. Nancy decided she wanted to contribute some gorgeous pink and orange iron oxide pigments to Ground Bright, minerals that she gathered in the early days of her pigment foraging and still had in abundance. Together we chose to direct the 22% donation to the People of Red Mountain, Paiute and Shoshone land protectors from Fort McDermitt Tribe who have been camped out for months on land in northern Nevada at the site of the proposed Thacker Pass mine.

Iron oxides collected and catalogued by artist Nancy Pobanz. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

interview with nancy pobanz

WPP: When you realized you could use the desert minerals you gathered while researching color for actual paint, instead of color-matching them with your acrylics, did you begin to do a lot of research about how to make paint from minerals? How did you learn, and what were the early days of your desert pigment use like?

NP: No, I did not do a lot of research. I was too impatient but was aware that minerals had been ground to a powder in centuries past. At first I mixed the powder with acrylic medium but the results were totally unacceptable for my use. I switched to making watercolor/gouache paint. It made more sense to use natural gum arabic from an acacia tree (even though I haven’t visited one) rather than a plastic (acrylic). Ultimately, after a great deal of experimentation, I researched the process in books and refined my technique.

WPP: Your pigments sets seem to me to be themselves your work. How often do you use the pigments you gather to make other work? Do all of the pigments have other applications or are some just part of the collections?

17.5” x 11.5”

Media: graphite pencil on watercolor paper; pigments collected in SE Oregon: OR hwy 31, east flank of Winter Rim; US hwy 20 milepost 178/179; Rimrock Draw Rockshelter archaeology site, unit 18, Harney County, Oregon; ash from Mt. St. Helens, 1980 eruption. Image courtesy of Nancy Pobanz.

NP: I don’t consider my pigment sets to be my work; they serve as references to the hundreds of colors that I’ve collected from sites that I’ve visited. However, the vials that I’m currently cataloging are ones that I use in my artwork, which probably doesn’t make sense, except that they are so easily accessible. I refill them after use. Since my artwork is about place and experience, the colors I select for a particular piece are ones that I found nearby or have some relationship to that experience. I use them in all my artwork about southeastern Oregon, where I grew up and now work with archaeologists.

WPP: Your sets of pigments in small glass vials have become iconic in the community of artists now gathering their own collections of pigments. How did the inspiration to create such a set come to you? Did you model the aesthetic of it on anything? What was your first official collection like?

NP: I selected vials simply because I had saved dozens of them from a Chinese herbal remedy for colds that I had been using. (Unfortunately they now come in plastic vials.) The size was appropriate and glass was my preference as I did not want to use tiny plastic bags.

WPP:: What is it like to have led the cutting edge of a material practice that’s growing in popularity?

NP: It never occurred to me, just like it didn’t occur to me when I started making Japanese-style paper from local plant materials in 1976 or when I introduced book arts to the arts community in the Philippines when I first moved there in 1985.

Pigments collected and catalogued by artist Nancy Pobanz. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

WPP: How do you categorize/record the pigments in your collection?

NP: By request of the scientists that I work with, I am cataloging my collection (a very tedious process!). Some colors are more desirable than others to use for pigments but they all reflect what is in the landscape. The cataloging involves grinding enough of the mineral to fill a vial. The second part is making a 3” x 4” card for each one with a rubbing of the powder, a smear of the watercolor/gouache paint (not available for most pigments), information about the location and a photo of me gathering the color.

WPP: What has moved you the most in your decades of gathering and working with earth pigments?

NP: What moves me the most is the direct connection between the collection of the pigment and the making of the artwork. It is an essential process for me.

WPP:Your work is closely aligned with science and scientists. How does science complement what you do as an artist, and why are you drawn to work with scientists?

NP: I’ve always been interested in various sciences, especially in regards to how art materials are made. The invitation to be the artist in residence at the dig was a rare opportunity; interactions with the large variety of scientists who visit the site provides the opportunity to learn about the mineral content and geological creation of my pigments as well as the many aspects of the archaeological process. It contributes a great deal to my work about southeastern Oregon.

20" x 15"

Media: Oregon earth pigments collected from US highway 20, quarry west of Hines; US hwy 26 adjacent to John Day Fossil Beds; (2) colors from Muddy Creek Ranch Rd, SE of Antelope; Rimrock Draw Rockshelter archaeology dig, unit 18; US hwy 20, Stinkingwater Pass; Steens Mountain summit; US hwy 95, 5 miles west of Rome; juniper wood ash from campfire, Andrews. Graphite pencil contour drawing on watercolor paper. Image courtesy of Nancy Pobanz.

WPP: You’ve been spending time out at the Rimrock Draw Rockshelter archeological dig in SE Oregon as the artist in residence every summer since 2016, where you’ve witnessed what was very likely a couple of mortars, with pigment embedded in their surfaces, as they were being uncovered. Can you tell me more about this experience, and what you’ve loved about being there? Why, do you think, is it important to have artists in residence at sites like this?

NP: Pat O’Grady, the lead archaeologist on this project, was interested in having me join the dig because he believes that the combination of art and science leads to a more holistic understanding of the project. Surprisingly, knowledge of the use of pigments is relatively new to archaeologists who generally don’t pay much attention to rock art (since they cannot date it unless the pigment has been used with a binder such as animal fat); Pat has also said that archaeologists consider the pigments used in pictographs to have come from some magical place. I have shown them that color is everywhere. While the excavation is going on, I check all bits of possible pigments (it’s like a pig sniffing out truffles: I don’t get to keep the colors!) and have taught the crew to do the same. At some point, geochemical testing will be done to compare my pigments with color used in pictographs to determine if there is a match. It would provide a possible source for the pigment. That my contribution of mineral pigments has become integrated with the project is very gratifying and not something that we anticipated. (My work at the dig is my own; I do not provide renderings of the artifacts.)

WPP: Do you think that there are any dangers to the current trend of foraging for and using natural pigments? How would you like to see people drawn to this practice behave, as land stewards and responsible citizens of the planet?

NP: Stay out of protected areas (national and state parks, national monuments, etc); do not collect on Indigenous reservations without permission, do not take more than you can use (which I did not realize when I first started collecting in 1996), do not disturb the landscape and leave some for the next explorers (i.e. do not deplete the source).

Thank you Nancy, for your thoughtful responses, your generous contribution to Ground Bright, and your excellent company! Much thanks to David, too, for the berries. :)

(end interview)

Foraged pestle stones in Nancy’s Studio. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

hello 22

Those of you who have witnessed my fondness for multiples of 11 will, perhaps, understand how chuffed I am about this year’s number. Celebrating my birthday on 1.11.22 is a number of a lifetime — it’s a cream and warm orangey-yellow number, to my synesthetic senses. Buttery. And there are some repeating-digit-bliss-like things happening this year from my vantage point here in the pigment community. A couple of big ones, that I can’t tell you about quite yet, but will in the next newsletter, so get ready!

Speaking of the next newsletter: it’s going to come up very soon. You may not have noticed, but the newsletters have gotten a little sparse these past few months, as I’ve been traveling and planning nice things I can’t yet mention. A couple of other pigment-contributing artists also had nice, very engaged things going on and were also very busy; too busy to do interviews, so I skipped a newsletter here and there. But don’t worry — I’m back on track. So, while this newsletter is still a couple weeks later than I’d like it to be, the next one — featuring an interview with none other than ink-maker-poet-slime-mold-whisperer-magician-philosopher-gun-melter Thomas Little of A Rural Pen Inkworks! — will come up very soon. I hope this won’t plump your inbox past capacity. Consider it catch-up, or an excuse to read and relax as we head into the year of the Tiger and celebrate the darkness (or brightness!) of Solstice.

Have your own personal foraging guidelines written down? I’d love to read them! You can email me any time at info@wildpigmentproject.org (or just reply to this email). I’d also love to hear your feedback about any of these mumblings, if they resonate, or don’t. Did you miss me? Should I stop sending you so much wordz?

Stay Reciprocal,

<3 Tilke

Nancy’s card catalog of SE Oregon desert pigments. Photo by Tilke Elkins.