pied midden: issue no.28 : mud memories : adi blaustein rejto

Ground Bright Pigments, photo by Tilke Elkins.

big exciting news

I’m bouncing up and down on my tail because I have something so exciting to tell you about that I really can’t contain myself. Nor do I wish to be contained!

Imagine a room, flooded with desert sun. The room is filled with paintings, sculptures, prints, and other ephemera, all made with foraged pigments. A long glass case in the middle of the room is the temporary home to more than thirty clusters of pigment families: the mineral, botanical, and waste-stream-derived pigment palettes of artists all over the planet. These objects and images are evidence of time-rich collaborations between artists/pigment practitioners and the lands they’re intertwined with.

Have you guessed what’s coming? A Wild Pigment Project exhibit, 2022! I’ve been invited to curate a group show this coming September at form & concept gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The show, which opens September 30th and runs until Novemebr 25th will feature work and pigment sets by all the artists who have contributed pigment to Ground Bright right up until then. And 22% of gallery and curator proceeds will be donated to Santa Fe’s Institute for American Indian Arts.

This is a golden event. More than anything, this group show is a window into the remarkable depth and collective innovative genius of the global pigment community. It’s a chance for these pigments to hang out together, in the same room, in real time and space, and share counsel, and for the people who learn with them to celebrate and take in the beauty of it all and each other.

It’s a very big party, with all my favorite people, rocks and plants, and you’re invited! The opportunity to orchestrate this exhibit is one of the most sparkling gifts anyone’s ever given me, so let me herenow express my infinite gratitude to form & concept gallery director Jordan Eddy, who extended the invitation, and to gallery owner Sandy Zane.

The gallery’s mission statement is all about breaking down heirarchies — which I love. See….

form & concept challenges the perceived distinctions between art, craft and design. We dispute the historic use of these terms to divide artists and rank material culture. Our programming acts as a conversation between many converging disciplines, harnessing the power of contemporary creative practice to shatter entrenched narratives.

Painter Heidi Brandow will be curating a show of Indigenous artists in the adjacent room, so there’ll be lots going on in the gallery at the same time, including a solo show of my own work (shiver!). I’m deep in preparation for that now.

Here’s the incomplete list of participating artists:

Melonie Ancheta, Heidi Gustafson, Caroline Ross, Thomas Little, Natalie Stopka, Amanda Brazier, Kelly Moody, Karma Barnes, Nancy Pobanz, Hosanna White, Brittany Boles, Lorraine Brigdale, Julie Beeler, Nina Elder, Lucille Junkere, Scott Sutton, Sydney Matrisciano, Marjorie Morgan, Joshua Ruder, Catalina Christensen, Adi Blaustein Rejto. Oh, and, Daniela Naomi Molnar, Sarah Hudson, and Melissa Ladkin (yes, that’s right, you just got a sneak peek of up-coming pigment contributors…!).

Go to the Ground Bright Archive for details about each of them. (Big thanks to my brilliant partner Noelle for putting this archive together.)

Inside the Restroom Light, by Adi Blaustein Rejto. Image courtesy of A.B. Rejto.

pigment as ‘ecstasy, delirium and resistance’

When I first saw Adi Blaustein Rejto’s paintings, I was struck by how singularly they captured my own sense of the essence of memory. Memory — the act of remembering, that prismatic, ever-shifting oil slick — has, for me, a taste, an atmosphere of textures and feelings. Ominous events can loom candy-colored, while deep comforts drift in a vague grayness. Space and time conflate, and emotions blur.

I love that Adi’s pigment foraging practice is so focused, mostly on one quiet earth pigment per painting, clays drawn from superfund urban sludge ditches or from the childhood creek where they sought refuge from family tensions. Contrasted with the synthetic pigments Adi uses, the clay mud becomes the stage on which all else revolves, the literal “ground” underfoot and under-paint, being both the (back)ground for the figures and the very earth on which they stand, the ground itself. There’s a theme of regeneration in all aspects of Adi’s work: the reclamation of poisoned soils as useable pigment, the transformation of personal traumas, and the shape-shifting energy of political resistance.

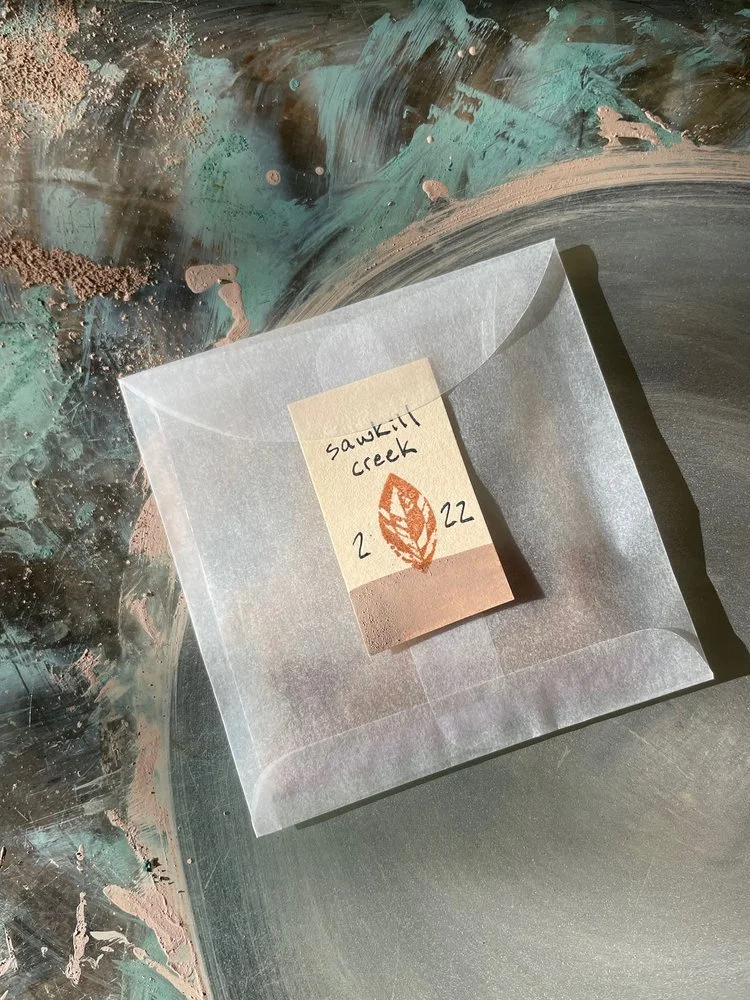

This month, Adi’s Ground Bright contribution is a milky rose-brown clay, dug from the bank of Sawkill Creek, where Adi grew up. Adi’s relationship with this clay is intimate, personal, chronologically layered, and memory-rich. It’s a reminder that beautiful pigment is everywhere, and that brilliant, saturated earths and mineral colors aren’t the only pigments worth relating to.

interview with adi

WPP: Adi, how were you first drawn to working with earth pigments?

ABR: I was still studying biochemistry and molecular biology at Hampshire College when I began painting. As I developed my visual voice, art making became a type of experimentation and learning process that was guided by my relationships and my own experiences. And in contrast, the scientific research process was guided by financing, myths of objectivity, and rigid reductionism in an environment that often demands complete devotion in lieu of a political and social understanding of research questions and institutional models.

So, as I lost interest in academic research, I became more interested in understanding the materials I was working with every day: paint and pigments, and my relationships with the world around me. And as I began to study and learn about the chemistry and history of pigments and paint, I began to learn how clearly imbricated layers of sociopolitical history, genocide and environmental destruction are sedimented in clay, waterways, heavy metals, and synthetic pigments. In pigments and paints are the stories of genocide and destruction. So it’s also with grief and gratitude that I touch the earth.

I started painting when I began to process and heal from the death of my brother, Julian, and the ensuing silence and violence in my home. In recording this healing process, I was needing to express what seemed like my first experiences of joy and pleasure, peace and fearlessness, growing out of traumatizing grief, fear, guilt and shame. Specific memories, conflicts, and places began to hold both grief and joy - and painting let me record these simultaneous experiences and became the guiding hand of my healing process.

I believe as David Wojnarowicz says « there is really no difference between memory and sight, fantasy and actual vision ». In my painting, I braid - present experiences of joy, pleasure, and the ecstasy and delirium of political resistance activity - with fantasized and remembered landscapes, places, and memories of myself and my family in pain.

In painting, time and space do become fluid and spacious, and I can provide whatever sort of attention I want, loving or spiteful, to my self or my family in a past memory. I can use clay pigment from a creek I escaped to as a teenager, and transform it into a subject of joy. A thing, embedded with life and earth, that people can dialogue with and form new ideas and thoughts. In both painting and paint making, it becomes clear that memory isn’t a thing that sits still in the past and stagnant in the mind and body, but is reconstructed and enacted by myself, now, with all my current relationships and experiences. Similarly, it’s in this space where grief becomes mourning. Mourning is a more active relationship to the internal experience of grief, that both touches into it and gives the grief space to move and change.

From Hutchin Hill, by Adi Blaustein Rejto. Image courtesy of A.B. Rejto.

WPP: What’s your foraging process like?

ABR: I primarily forage pigments in the Catskill mountains where I grew up, from specific places I would go to for comfort, for a sense of agency, for a spacious quiet rather than a suffocating silence at home. Coming back to these places, now with personal practices, meditating with them, and gathering earth, clay, and mud that I can transform into paintings creates a new and rich relationship with these places.

So the pigment I’m sending out through Ground Bright is from one of these places: the Sawkill Creek, a tributary to the Esopus Creek, that feeds into the Hudson River. Since I’m white and an occupier of this occupied and stolen Lenape land, I don’t feel comfortable giving formal land acknowledgements nor using the Munsee name of the Esopus, Atkarkaton. The truth is I don’t know the story of this land and the people and life from whom it was taken, and in the midden of confusing feelings I have about stealing even more land from this earth – I know how important this land has been for me.

I have come here when I didn’t know where else to go. To be held by the creek and the quiet woods. And I’ve come here to celebrate, I’ve brought loved ones to have fun and be joyful. And I come here to sit with my hand in the clay on the bank of the creek and my feet in the water. I wait until I feel a warmth in the earth and then only take what I need, often only a jar or a cookie tin.

To get enough pigment to send in this batch, however, I had to get a bit more. I foraged the first half in October 2021, when the ground was still warm and the water was…moving. When I returned in January, the water was frozen, the rocks were covered in ice, and the clay was cold. As someone who is often not prepared, I didn’t have any crampons and couldn’t cross the creek to get to any of the clay that was on the bank of the creek. So, the other half of the pigment is gathered from clay that was closer to the woods and the roots of trees. I’m assuming that this has less natural clay binder and may make a weaker paint film. But regardless, it is Sawkill pigment.

Being a House Fly, by Adi Blaustein Rejto. Image courtesy of A.B. Rejto.

WPP: Can you describe one of your more urban foraging moments for me?

ABR: It’s February 26th, my birthday, and I’m squatting on a rock in Newtown Creek, with gloved hands, scooping sludge from this toxic superfund site. All I can hear are the cars on the nearby highway and the train above me rumbling by. The oil in the water makes the sludge in my hands flicker with blue, pink, and yellow hues. Back in the studio, the sludge is spread out on a drying rack before it is ground by mortar and pestle. After washing and filtering away the petroleum and pollutants of the water and land, I’m left with a deep brown pigment and gratitude towards the devastated creek.

I love foraging because I believe everyone can relate to it; it is so deeply present in all of our lives, industry, economics, chemistry, and all history. And projects like that of John Sabraw and Onya McClausland inspire me so much. Transforming pollutants into pigments is exactly the sort of work I want to do- bringing communities together to remediate their poisoned land and water, and to create new artist materials clearly situated in society. To me wild pigments are a perfect home for me, where scientific research, spiritual practices, artist materials, and political resistance, violent histories, and community organizing are all sedimented together.

You Must Not Be Seen, by Adi Blaustein Rejto. Image courtesy of A.B. Rejto.

WPP: The phantasmic hues of the petroleum slick on the mud reappear in your paintings as synthetic pigments mingling with the rich clay pigment. You replicate a visual experience that’s so familiar to so many of us: the haunted, poisonous-yet-alluring day-glo flickers of petroleum plastic colors against the very different palette of muds, minerals, plants and decomposition. The contrast, it seems to me, holds the contradictions of abuse and joy, disruption and pleasure that you talk about.

Tell me a bit about how your foraged clay pigment appears in a couple of your paintings…

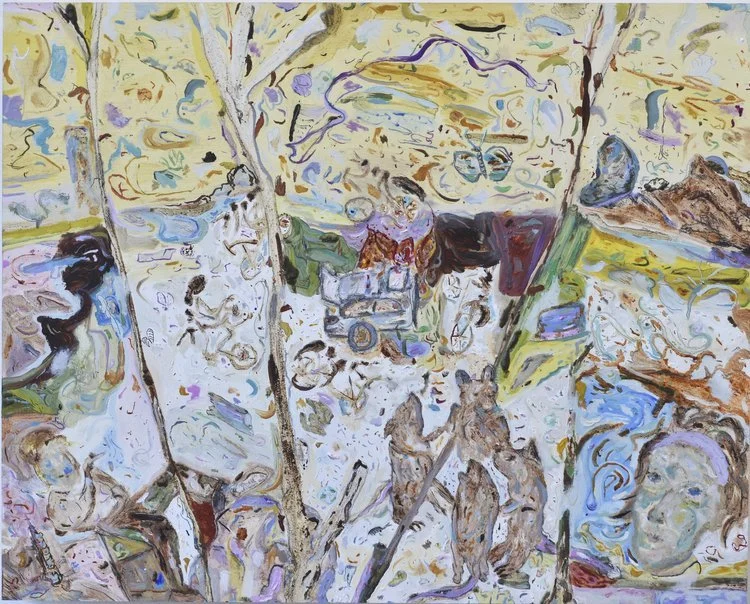

ABR: Mixed with walnut oil, this paint becomes the first layer of Inside the Restroom Light, a painting in which, in an atmosphere without gravity, among moving pieces and flying insects, my grief-filled and abusive parents, tucked away in the bottom corners, are thrown into a moving set of revolutionary ants on bikes, vermin celebrating their resistance against abuse and violence. My paintings draw not only from the damaged environments many of my pigments come from, but simultaneously process and transform my own traumas and experiences of grief into expressions of joy and pleasure, moments of revolution and celebration, and spacious worlds where change is visible.

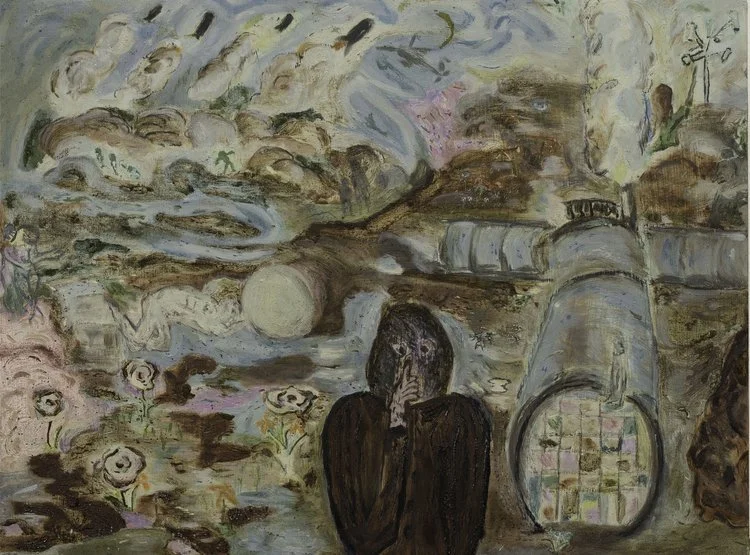

My most recent painting is called You must not be seen. The title comes from a line in a learning-play I’m acting in, The Measures Taken, by Bertholt Brecht. It depicts someone throwing an object in a chaotic scene, forcefully and with wind and movement. Supporting them are some friends, perhaps comrades, a group of sweet demons. And embedded in this character is another image of the action, but still and sharp, like a surveillance image of the act in progress. In its most basic bones, I’m using homemade oil paint made from pigments from Sawkill Creek predominantly, and store-bought oil paints, to create a scene expressing anger, violence, conflict - and the poisonous cultural system of surveillance that keeps people oppressed.

WPP: I’m really interested in what you say about this transformation of trauma and grief into expressions of joy and pleasure. Does this transformation begin inside the painting, or earlier? What brings it about?

ABR: Well, the trauma and the grief don’t transform, the thing doesn’t change, but my reaction and the feelings that arise in my body when I remember or am back home, are different. When I work on a painting, it’s like a long meditation, where suddenly there’s some space around the subject of my attention: it becomes lighter when present with an experience whether that’s grief, longing, rage, or even joy. Importantly, this process of painting is full of joy, agency, and freedom. In this place, I have the power to reconstruct my experiences with my own voice, where things don’t really have to make sense. Where time and space are muddy and watery. And where out of this confusion, light, wisdom, a sense of spaciousness, joy, and gratitude arise.

WPP: Has working with mud changed the way you perceive mud colors?

ABR: Yes, I love mud colors, I love earth tones, I think they create a ground, a base, a source of depth and contrast that brings the painting to life as other colors flower on top of or beside the earth colors.

WPP: One more question: Can you tell me a bit about the organization you’re directing your 22% to? How does it function as reciprocity to the land, for you?

ABR: I’d like to donate the 22% to Frack Out of Brooklyn. It’s a Black, Brown, and Indigenous-led organization, currently fighting against a natural gas pipeline proposed in North Brooklyn, from Williamsburg to Brownsville. There is a coalition of organizations currently fighting against the pipeline, but I won’t say I’m optimistic. Regardless, this coalition has plenty of legal fees, among with other campaign costs. Though this isn’t a donation directly to Lenape or Munsee people, or organizations in the Catskills, I want to support my neighbors and comrades in their overwhelming and unending fight and advocacy for the earth around us.

WPP: Thank you, Adi. I have huge appreciation for your work, for the many layers present in your paintings, and I feel so much of what you describe as your process when I travel into the world they contain: the coexistence of grief and joy, held together by the aesthetic succulence of your rich visual vocabulary. Thanks for your many insights, and the gift of Sawkill Creek pigment.

(end)

Flotsam from my ‘Being With Pigments’ course this Solstice season. Photo by me.

solstice sessions send off

As I surface from the intensity of teaching a six week Being With Pigments course with 36 wise, focused, irreverent pigment revolutionaries at many different stages in their pigment journeys (in two separate groups!) I’m still humming with the power of our shared time together. Spanning multiple time zones and circumstances…nursing babies, wrangling toddlers, recovering from forest fires, struggling with covid, despairing over poisoned water supplies, rejoicing about major life transitions, devoured by logistics, tucked in by mountains of snow, lonely, content, peaceful, skeptical, protective, laid bare…. risks were taken on those tiny screens, vulnerabilities were shared.

One participant, Jill Kuanfung, wrote a poem about the course that is arm-hair-raising. Jill is a very good painter and poet.

Jill wrote:

I was thinking about everything I learned and felt during your course and I wrote this poem:It turns out the rocks are ready

to make color

(you don't even have to alter them).

Their wet grit rubs off with a gentle scratch

(sidewalk chalk in the rain).

I rediscovered brown today.I wish people gushed

over it more.

I wish no one ever

called it ugly.

The earth might

even love it best.

(Why else would she make it

over

and over

and over?)

I tried to strain somemold from a jar

I got in a rush

It slithered back

into the mixture

I had to start over

I had to start over.

I wishI could start

over with the grace

of the earth

who faces loss

at every turn

who builds the most

intricate things and watches

them die

every year (in addition

to being poisoned).

I never thought to painton a leaf

or the hidden parts

of a branch.

I never thoughtof a cat person.

It turns outthere is cow

in some types

of glue.

I have been suppressingmy mourning

of felled trees.

I haven't been moving fastonly skipping

through. There is no heat

in my muscles. Only a feeling

that I missed

something important.

I'm starting over.

This timeI'll catch the mold

This time I'll wait

for the last drop

I wasn'twho I thought

so I peeled up

the bark

and found green

I thought I got coal because I was bad.I began to accumulate it

on the mantle.

Little piles of shame.

Today I pickedone up.

I crushed it in my mortar.

I made a new black.

I painted the newborn ink.

It turns out

I was ready

So many thanks, Jill, for writing this and allowing me to share it.

Your emails are a delight. If this issue sparked something for you, I’d love to hear it. Write to me at info@wildpigmentproject.org.

Stay Newborn,

<3 Tilke

Ground Brights. Photo by Tilke Elkins.