pied midden: issue no.27 : paper tigers : thomas little

Thomas’s hand covered in the wild ochre component of ‘Paper Tiger.’ Image courtesy of Thomas Little.

cut to the (tiger) chase

Uncharacteristically, I’m going to keep my introductory blah blah to a minimum this month and go straight into the excellent interview with ink maker and alchemist Thomas Little, of A Rural Pen Inkworks. Many of you are familiar with Thomas’s work. Those of you who aren’t, I recommend spending time scrolling through his Instagram feed — it’s hands down one of the best of its kind. You’ll see slime mold beating like an open heart, guns dissolving in sulphuric acid, money in blenders, and lots of great art.

Thomas is also a writer who has written extensively about his work. Be sure to go back to the Pied Midden archive and read his fascinating musings in issues no. 4 and no.17.

interview with thomas little

WPP: So, Thomas, what can you tell me about the name of your most recent pigment contribution to Ground Bright — ‘a synthesized yellow iron oxide derived from an early 20th century shotgun manufactured by the Crescent Firearms Company, and an iron rich sandstone outcropping in the Cohairie River basin’ ?

TL: I named this pigment ‘Paper Tiger’ for many intersecting reasons. I have loved tigers, at least abstractly, since childhood. Most likely because "Tiger" starts with a "T" like "Thomas". An origami paper tiger was one of my favorite toys to make and play with as a child. I made lots of origami toys, mostly because I would take them into the tub with me to play with them, where they would promptly fall apart. The tub was stained with rust streaks, as we have lots of iron in our well water. The yellow/orange stain was everywhere, and as I grew up I began to associate it more and more with being poor. It was in our tub, or sink. It stained our clothes. It would pool on the concrete floor when my father had to replace a leaky car radiator. When I was a teenager, the color would depress me. I learned the term, the metaphor, "Paper Tiger" in school. Something that appears frightening, but is in fact not threatening. This never really rang true with me. Sometimes, when you're vulnerable and poor, just the appearance of something frightening can be harmful. So I began to think of paper tigers, how they would hunt. They would be ambush predators, like real tigers, but they would not kill quickly. Paper Tigers kill through a thousand cuts. Their stripes, on walls from leaky gutters, or on porcelain sinks, would haunt me, remind me of hard times, always dirty shirts. This is perhaps why, even now, as a pigment maker who has (somewhat) outgrown his moody teenage years, I never made significant quantities of this tawny yellow color. I use it in my artwork quite often, sure, but I try to be sparing with it. It is always easier to work with dramatic blacks and reds, easier to talk about them.

WPP: This description is such visual poetry and would make a really elegant puppet show or stop-motion animation. It has so many turns of transformation in it: the origami tigers dissolving into the bathwater, becoming the rust streaks, becoming the paint that makes the tigers’ stripes, becoming the live paper tiger stalking its prey, becoming the sadness…

Until I was five, we lived next door to a Shell gas station in a worn Victorian house whose front rooms were occupied by Martin’s Locksmith. The smell of home was the sweet round grey smell of the oil used by the keying machines and the bright fumes of the gas pumps. The cigarettes of the old woman who smoked and watched me while I watched Sesame Street from my high chair while my parents worked. The cat pee in the secret corners of rooms, the leaden smell of snow in drafty crevices. Pigeons gathered on the windowsills, and rotten apples buzzing with wasps collected in the weed-filled space behind the house. Rust, dust and these other atmospheres are coiled in my memory, and are associated with loneliness and drear, a city grayness. In contrast are the brilliant yellows, blues and reds of the house paint my parents used to cover up the neglect…and the brilliance of the cartoon T.V. worlds I was lulled by. The association of bright color as an antidote to abandonment has lasted for me. Only in recent years have I allowed myself the pleasure of subtle, minimalist greys. Our color associations run deep.

Next question. Your work as an ink maker draws from both science and the occult, and has its roots in theater. Speaking of childhood, and iron, can you describe how your love of magic and slight-of-hand as a kid became the umbilicus for your love of ink?

TL: I suppose, with the help of hindsight, the work I do could be tied to a fifth grade report on Harry Houdini. Part of the report was a kind of presentation, I can't quite remember specifically. I wanted to perform a color changing liquid trick, known as the "water to wine" trick. It was in essence an iron tannin reaction, using ferrous sulfate and tannic acid (there was a part where it was supposed to turn back to water and then to wine again using oxalic acid and ammonia, but I bungled that part). This was due in December, around my birthday, and my dad thought it would be a nice birthday present to make up a chemistry set with the components of the trick. This was before the internet, online ordering, wikipedia and all that. He went out and did a county wide search through all of the old pharmacies for the chemicals, and I had everything I needed. The report was passable, but not particularly popular, as I grew up (and still live) in the Bible Belt, and performing one of Jesus' miracles was rather frowned upon. (For some reason, as part of the trick, I had a skeletal fetus made out of homemade play dough and an ostrich feather as well, which might have been a bit off putting. What can I say? I was a budding Gothic Romantic.)

Inks and pigments by Thomas. Image courtesy of Thomas Little.

WPP: Magic, it seems to me, uses science to call up the unknown. Conjuring an awareness of mystery, rather than the small (or large) glories of the actual tricks themselves, is the true goal of the magician, would you agree? If so, does this resonate for you in the forms of art you practice these days?

TL: I don't know if I can speak of a magician's goals, as I don't really know if I would call myself a magician. Though I guess that would depend on how one would define magic and a person who practices it. Conjuring an awareness of the mysteries of the universe, the spirit of things, inviting others to witness and wonder... Those things are a noble definition of magic, and that pursuit would be a worthy goal of such a practitioner. But even within that definition, I would have to exclude myself, somewhat, as ultimately it is for selfish reasons that I pursue what I pursue. It is my insatiable appetite for wonder that I indulge in these excursions, in art and what not. Though, I could, perhaps, find redemption in the fact that, unlike the stage magician who jealously guards his secrets, I gladly share whatever discovery delights my curiosity.

WPP: I’m interested too in how the works of 'dark romantic' or gothic writers have contributed to your dialog with mystery in its many forms: ink blots, radio waves, scrying, eukaryotic organisms, and unlikely chemistries. What is it about the gothic approach to mystery that compels you?

TL: The gothic approach to mystery is a perfectly apt metaphor for the human condition in this universe. Are we not wandering through a cavernous and dark chamber with but a tiny candle flame to explore it with? It's terrifying and thrilling, this world. I would add that the branch of dark and gothic romance I find the most compelling is the one that is close to bifurcating into either the supernatural or science-fiction. It is a place where the imagination hesitates between taboo and enlightenment.

Ink bond: magnetite and Physarium with pigment. Image courtesy of Thomas Little.

WPP: Ah, taboo! Might you crack the door open and shine a ray of light on some of the edges of taboo/enlightenment you're riding these days?

TL: I would venture to say that such an edge lies in the deconstruction of ritual technology. The physical objects and protocols surrounding traditions, either orthodox or more fringe/folk, I think are tantalizing. For example, the blood of San Gennaro, sealed in an ampoule, that liquifies three times a year. What is its chemical composition? Is it an iron oxide compound? What alchemist was commissioned to create it? Or is it, in fact, some holy blood? This touches on your description of magic earlier. Does it matter if it's a cheap parlor trick if it still brings an awareness of the unseen world? What separates an official miracle from pasteboard magic? This line of inquiry would certainly be taboo for the faithful, I would imagine. But if the hierarchy of so many religions was reconsidered, removed even, and the profane was seen as another side of the sacred, then the sharp line between miracle and trick would blur. And the intent of the practitioner (magician or priest) would become evident. Is the intent to deceive and indoctrinate, or to allow a glimpse into the realm of wonder and mystery?

WPP: I love the engine of miracles that this 'deconstruction of ritual technologies' sets up, where, as you suggest, the chemical alchemy of a material that liquifies periodically on schedule might be more a proof of the divine than the blood theater of a saint. I sense this sort of miracle spreading its roots with your physarum collaboration. I'm curious what your work with Physarum polycephalum -- also called "slime mold," though it's neither a slime nor a mold, but a biologically immortal, 780-sexed population of amoebae -- has uncovered this year, since we heard from you last in issue no.17. Now that your relationship with Physarum has deepened, have patterns emerged that suggest correspondences between the shapes made by slime mold and those revealed in ink blots? What insights, or new mysteries, have come to light through these commingling acheiropoetica?

Slime mold responding to ink blot. Image courtesy of Thomas Little.

TL: The work with the inkblots and slime mold looks very much the same, but my perspective is ever changing. When I started making them, I knew there was something important, something worth paying attention to. Making them into art documents was a fun way to share them, and hear what others thought of them. I took a hiatus over the summer, but returned to working with the Physarum again at the end of October, and the work continued seamlessly. It is nice, I suppose, to have the art just make itself, with the only pressing concern of mine being when to feed it and when to evacuate it from the paper. But like with most custodial jobs, one tends to get philosophic.

There is so much rich metaphoric content in these simple pieces, I have a hard time following one thread before another presents itself. Early on, I saw them as anatomical diagrams of some kind of imaginary creature, flayed and pinned with its viscera exposed. More recently, I've been thinking of them through a more spiritually contemplative lens. One of the more popular tricks the slime mold performs is maze solving, and I began thinking of the blot as a type of maze. This recalled a type of document that I had come across early on in my pigment studies, the Geistlicher Irrgarten, or the Spiritual Labyrinth. These were documents printed by the Pennsylvania Germans, meant to be both decorative and edifying. They were texts printed as a path, with the words running horizontal, sideways and upside down, to form a labyrinth. The content of these texts was a kind of paper pilgrimage, where the reader was led through the earthly garden of life, avoiding pitfalls of sin and occasionally being nourished by the wisdom of scripture. The overarching theme is an obstacle course for the soul where one would find redemption upon satisfactory completion of the labyrinth. As I began to view the inkblot as a maze and slime mold as a maze runner, I started to think of what those components really were. Was I taking the role of God-as-Scientist, testing the virtues of this humble brainless creature with my inkblot maze? That wasn't exactly correct. In fact, the more I examined the pieces, the slime mold was, in a way, generating its own maze, the networks of ectoplasmic tubes that it pulses nutrients through. Answering a maze with another maze. So it was more of a correspondence, a dialogue of forms, than a test. And by removing that kind of hierarchical thinking, I began to understand these pieces as truly edifying documents.

Scroll made with Thomas’s “somber little rainbow”: red, black and yellow. Image courtesy of Thomas Little.

WPP: Your contribution, this month, of Paper Tiger, makes you the very first three-time contributor to Ground Bright, Wild Pigment Project's pigment subscription. Congratulations and huge gratitude to you!! Your whole-hearted support of this project has really enriched the yearly cycle for me. Paper Tiger also marks the third of the set of pigments made from dissolved guns, following Telephic Red, and Sable Wave. Can you say a little about the symbolic import of this trinity?

TL: Black, Red and Yellow... the Mars suite! As a student of alchemy, there is the association with these colors being three of the four of the Magnum Opus (the other is White). In working with Iron compounds, I imagined this as being my own great work. Though humble in terms of chemistry, I find engaging with this metal and playing with its different valences, I can appreciate the ways it works as a life form molecule. It's a somber little rainbow, but to me, it colors a whole world.

WPP: The somber little rainbow. So apt. How does dissolving firearms address your personal/familiar relationship with guns? Have you felt any shifting in these histories since you started doing this work? What sort of epiphany led you to the gun-to-ink alchemy?

TL: When I started dissolving firearms to make pigments, to be truthful, I just wanted to see if I could. I was influenced by the "swords to plowshares" idea, but I wanted to take it further into abstraction while still closer to the earth. Reducing weapons to oxides of iron is natural as can be. I sometimes think of myself as an agent of accelerated entropy, a fast acting ruster. Guns have taken loved ones from me and so many others. I have personal reasons why I do what I do, but these days I don't really think about it too much. I'm more excited about making the prima materia of the gun completely anonymous, just color, just dust. And then using it to make things that are more compelling (I hope) than what the original object was. I was a product of guns. My mother met my father while he was doing gunsmith work in her father's basement. But I am more than that, just the way a line of ink can be more than what it's made of. It's funny that I am talking like this, as I know Ground Bright and Wild Pigment Project are about connecting color substances to the people, places and things they come from. I seem to be spouting heresy! A damnatio memoriae of materia! But I think that has its place too.

WPP: I think some vulnerabilities need protection. I appreciate you as an usher of dark energy, which you lead towards transformation. It makes sense that this role requires personal knowledge of the effects of the appetites of darkness.

Last question: You have some exciting stuff happening this year. Is there anything you want to give us a peek into.?

TL: There is a group show I am participating in for the month of May at the Amos Eno Gallery in Brooklyn, NY. I was offered the privilege of showing with two amazing artists, Candace Jensen and Coleman Stevenson. While the ideas are still gelling, we are working roughly with the concept of viewing the more-than-human world (natural and supernatural) through the lens of manuscript arts. I feel like I fit in well with these two. Candace produces sumptuous pieces of liquid calligraphic beauty, while Coleman builds these minimalist instruments with spidery engineering and ritualistic intent. We open on May 6th, I believe. We'll see where we are in the spring of course. Aside from this, I will probably keep doing the same thing, melt guns, make colors, feed slime monsters etc. I've been liking this groove I'm in. But that will change, I'm sure. Ha ha.

Rudy in his nest. Image courtesy of Thomas Little.

WPP: Well, you are a wealth of variation, it’s true! But maybe it’s like my Canadian grandma used to say: Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose.

Hang on! I have one more question! It’s about Rudy, the pot-bellied pig who appears regularly in your Instagram feed. How did Rudy come to be part of your family, and what sort of role does he play for you all?

TL: We found Rudy in a field of peanuts. He was most likely abandoned. He is very business. He has a very well-established routine that gives my brother and father an avenue of small talk that we engage frequently. We find his daily activities mysterious and noteworthy. We all care deeply for him, even though he can be a bit of a fuss pants.

WPP: My family lived with a pot-bellied pig named Victoria for 18 years. She was supposed to be “mini” but turned out to be 120 pounds. We adored her.

Thank you for indulging all my probing questions, Thomas!

(end)

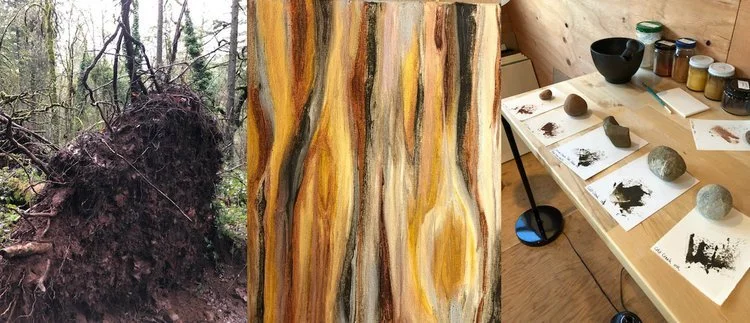

Croisan Creek, Painting with Foraged Pigments, Studio View. Images courtesy of Jana Carp.

letters to the editor

Tilke,

I wanted to let you know that this particular newsletter was more meaningful to me than simple enjoyment. This is the story, which I'm offering to you as a big thank you note!

When we had to cancel my birthday trip to the Olympic Peninsula after Christmas, my husband suggested that I take those "vacation days" as an artist's weekend -- he would take care of everything so I could spend three days straight in my studio. I knew immediately what I was going to do with all that glorious, distraction-free time: make pigment from the rocks I had been gathering. I have been circling in on using natural pigments for about two years but even though I made a bunch of tubes of oil paint from Natural Earth Paints and some dirt and leaf rubbings and collected some black walnut fruits, I hadn't really felt that I was doing what I needed/wanted/desired to do. What was different this time? Your newsletter had readied me in the way I needed. I don't know what it was exactly -- maybe the term "reciprocal foraging", maybe gratitude for how you connected foraging to a "pre-foraging" practice, maybe affirmation of my experience of conversation with the things I notice and want to take, maybe the comfort of an overview of the practice from preparation and attitude to clean-up. (Maybe the slow drip of pigments and stories from Groundbright is having an effect, too!)

I took seven small rocks that I had picked up, mostly from my son's farm and one from the roots of a fallen tree at the edge of a trail in my neighborhood. I rummaged for something rough and found a big, 4" screw, and I started rubbing it against the first rock. A little pile of powder formed! Long story short, five of the rocks were easy enough to grind in that simple way and provided two reddish pigments, a black one and two light green. The next day I mixed my foraged pigments with walnut oil. I ended up with two very similar reds and three blacks. But mixing the green-to-black pigments with titanium white made the most beautiful green-greys. Finally, I made up a storage box for the rocks and their info cards. I can't wait to get back to it.

It's taken me two years to go from "I'm just not going to use acrylic paints any more" to this first encounter with local rock pigments, and all during that time I have been trying to figure out who I am as an artist, that is, how to suspend judgment. I didn't have any idea how meaningful it was going to be to co-create with wild pigments; it feels like what I've been missing, this sense of mutual co-expression. ("Being with"!) And I know I'm just at the beginning. I'll work along for a while, doing what presents itself as a next step (like a finer grind) and when I have built up some experience I'll dive into your beautiful website and perhaps some research.

But for now,

heartfelt thanks.

--Jana

p.s. This is the painting I did, with no real ambition but to learn from these wild pigments. I supplemented with titanium white and yellow ocher paints that I had made earlier (Natural Earth Paint).

Thanks Jana! This, as I said when I wrote back to you, made the hair on my arms stand up. Thank you for your generosity of story-sharing, and for agreeing to share your letter and photos in the newsletter.

so long

That’s all for this month, dearest readers. I always thrill to hear from you. If you feel like writing, you can reach me at info@wildpigmentproject.org.

Stay In Your Heart,

<3 Tilke

My studio in winter. Image by Tilke Elkins.