pied midden: issue no. 33 : returnings : melissa ladkin

Image of gudjing (red ochre) courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

long way

I’m devoting the entirety of this month’s newsletter to the words of contemporary artist Melissa Ladkin, a proud descendant of the Awabakal / Wonnarua / Bundjalung peoples in so-called-Australia. Melissa is a painter who gathers and works closely with ochres.

Since February, Mel and I have been in conversation, through Zoom, emails and voice mail messages, about what it might mean for Mel to contribute pigment to Wild Pigment Project through Ground Bright. The subject of protocols and the sharing of cultural knowledge around ochres is complex and sensitive. I’m immensely grateful to Mel for all that she’s shared here, and through the contribution of pigment.

Mel has named her contributed pigment ‘Gayuli,’ a Bundjalung word for ‘long way.’ She’s directing the 22% donation to a powerful organization, The Returning, owned and run by Indigenous women (more on that below). Gayuli is a long way from home, and soon will travel once more, to subscribers in more than 14 countries. Our conversation, over the past several months, has focused on the significance of ochre in Bundjalung and other First Nations cultures, and the implications of sending ochre a ‘long way’ from its place of origin. As you may know from reading this newsletter, the question of what it means to take what I call ‘wild pigments’ from their places of origin is a big one for me. Since variations of this question form the body of my side of the dialog between me and Mel, I’ve chosen to leave my own words out, in this version. They include much gratitude to Mel for this conversation, for her support of this project, for her many kind words about my work, and for the deep love and care she shows the planet and the beings here. Thank you, Mel.

At some point in our dialogue, it occurred to me that we might invite Ground Bright subscribers to enjoy Gayuli for a little while, and then, if they wished, send the ochre back to Mel (through me) to be returned to the land. This is a radical departure, a new direction for Ground Bright, and a seed that I hope might grow. It invites an entirely different relationship with pigment — one that I’ve been exploring in my own work for a time.

What follows is two documents. The first is the text about Gayuli, written by Mel to accompany the pigment when it’s mailed to subscribers. This feels important to include here, to contextualize what comes next: a series of voice messages from Mel, which I transcribed and passed to Mel for further editing (with non-USA English spellings preserved). The last one was sent just before Mel embarked on an important journey to the northern part of the continent, which she refers to. These messages really give the feeling of our conversation, and I’m honored to share them with you now.

But first, the Gayuli card text…

‘Gayuli’ pigment. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

ABOUT THE JULY GROUND BRIGHT PIGMENT: GAYULI

The unceded land upon which this gudjing (red pigment) was collected with permission is that of the traditional owners and custodians, The Bundjalung peoples of The Bundjalung Nation.

Australia consists of over 350 different Indigenous nations, each with clan groups who have their own distinct dialects. There are some 600 plus languages across the country.The Bundjalung language belongs to the Pama-Nyungan family of Australian languages. At the time of first contact with Europeans there were up to 20 dialects of the language, which included the Wahlubal, Yugambeh, Birrihn, Barryugil, Bandjalang, Wudjebal, Wiyabal, Wuhyabal, Minyangbal, Gidhabal, Galibal, and Ngarrahngbal dialects.

The arrival of Europeans in the 1840s had a dramatic impact on the lives of The Bundjalung people. From the 1860s, their lands were cleared and fenced, forcing them to live in camps on the edge of these newly formed towns. Sacred lands and hunting grounds were involuntarily turned into someone else’s property and families were torn apart to an extent that still impacts the new generations.

The Region (Far North Coast of NSW, Australia) covers an area of 10,293 square kilometers. The climate is generally subtropical, with warm humid summers and mild winters, a marked summer and autumn rainfall, relatively dry springs, and fine sunny days with cool nights in winter. From east to west, this region is characterised by coastal alluvial flood plains, rocky headlands, dune fields, lakes and estuaries, to midland hills and in the west and north, escarpment ranges. About 47% of the Far North Coast Region is covered with native vegetation in varying condition. The north-eastern area is characterised by the eroded caldera of Wollunbin (Mount Warning) and the associated highly and moderately fertile volcanic-derived soils.

There are three major river systems in the Far North Coast Region: The Upper Clarence, the Richmond and the Tweed. These rivers are stressed to some degree due to interference with flow patterns, water extraction, riparian degradation and reduced water quality.Since the 1850’s when the Far North Coast of NSW was ‘settled’, it has predominately become home to a range of primary industries, including agriculture, forestry, mining, and commercial and recreational fishing.

This gudjing (red pigment) was collected with respect and acknowledgement from a seam in a disused farming dam before the horrific floods of early 2022 in the area. I had not quite collected all required but when the flood hit, land slips presented all over the shire. The whole side of the hill fell into the old dam and covered it entirely with no sign of the seam anywhere. It seems the ancestors had spoken…

Image courtesy of Mel Ladkin.

(continued from above)

We (my people) never take without the rule or lore of giving back to the land in some way.We have upwards of 60,000 years of having a reciprocal relationship with the land. It warms my heart that the recipient of the Ground Bright donation for this Gudjing (red pigment) will be going to someone very dear to me and the community of The Bundjalung Nation.

Ella Bancroft is an Indigenous change-maker, artist, storyteller, mentor and founder of “The Returning,” active advocate for The Decolonisation movement. She is widely respected amongst her community and believes in local communities with local economies as a way to find hope for the health of our planet and people.

The Returning is a Not-for-profit, grass roots collective that runs cultural camps for Indigenous peoples. It is also an event that takes place just outside of Byron Bay, Australia, providing a place for all women, all walks of life to come together to relearn the way of their past, to connect to herbalism, activism, motherhood, health, movement and deep connection to the land.

I pray that these ochres travel gently and land lightly with respect to ancestors & traditional owners of those lands.

When using this gudjing in your practice may I ask that you also pay respect & consider where it has come from, Bundjalung Country. May you consider the knowledge and wisdom it holds and speaks of. To all the ancestors who have come before, walking lightly on & with the lands of The Bundjalung peoples. To all we may learn from it and continue to practice from the stories it holds and the guidance it gives. Continue to ask deep questions within your own practice regarding the origins of your pigments & ochres, whose lands they come from, the names of them and their stories, spirits and sentients.

This gudjing has gone through ceremony and cleansing before leaving country.

I respect & understand that each different nation/clan/family group has its own history, traditional cultural practices, protocols and spiritual beliefs to ochres.

I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and recognise the continuing connection to lands, waters, skies and communities.

Pay deep respect & acknowledge my connection and ancestral ties to the lands that I live on and all Indigenous peoples globally.

…This always was, & always will be Aboriginal land….

Melissa Ladkin

Awabakal / Wonnarua / Bundjalung

April 2022

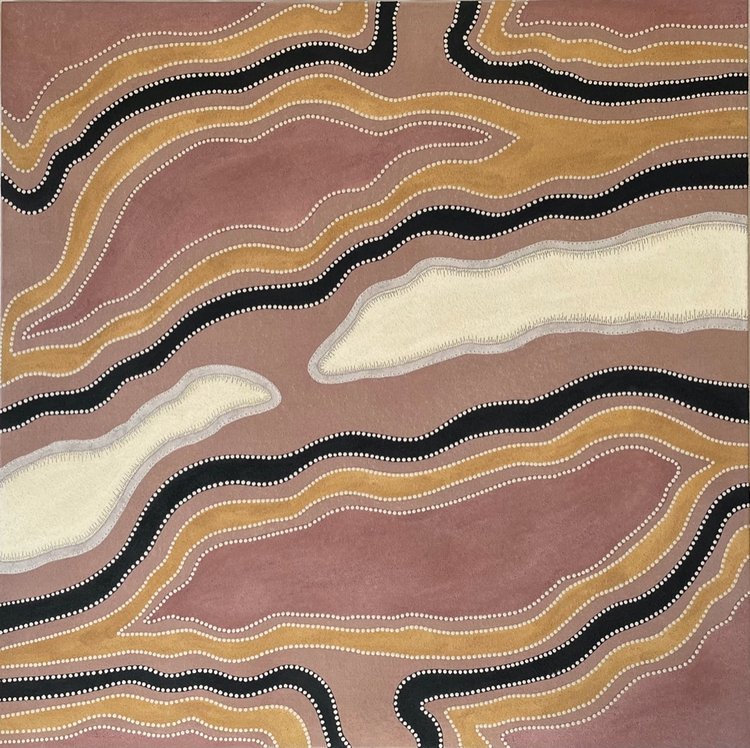

Palapai — valley; ochre on linen, by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Mel Ladkin.

on pigment & protocols : more from melissa ladkin

The following was received as voice mail messages & emails between February & July, 2022.

Hi Til!

I thought I'd send this voice mail just because it's a little bit easier to communicate than typing so much. Life is a little bit busy. I work 2 jobs full time and paintings on the side, volunteering, a family with the ongoing complexities and the world with the current situation of COVID is quite something for all right now.

Firstly, what comes up straight away for me [in thinking about what contributing ochre to Ground Bright might mean], is our people are all so deeply connected to country, in all of its forms.

There is no separation — country does not just mean ‘the land.’ It includes all living things, people, plants and animals. The sky, all waters, it incorporates all the seasons, stories and spirits.

It is a belonging to and a way of believing.

There are many protocols with all use of country and all First Nations peoples are very different in the way they have a relationship to cultural practises. Some feel very strongly about the use of ochres and pigments and that some should not be used out of ceremony or be taken off country. I can receive negativity and sometimes outrage that I work with pigments. I have to constantly be accountable and mindful of the complexities of each different clan/nation group and their personal relationship to ochres.

We as a people must always follow protocols and ask permission with everything we put out into the world. It can be a really tricky navigation and you do not always have a ‘yes.’

The way that I navigate that currently is just really asking, asking permission and knowing in my heart, where I come from and what my practice is, and having a really deep understanding of my practice and of also earth pigments, and ochres.

I've had my hands in soil constantly, probably most of my life actually. I've been a bush regenerator for over 30 years and always had a deep fascination with soil and geology. I’ve been giving back to the land in that way, planting well over half a million trees personally in my career, caring for country in many ways. I also work for an organization, an NGO in Nepal called Hands with Hands. So that takes up a huge chunk of my time too. Having that custodianship of the land and how I use my painting, also my offerings to educate others and to share knowledge, I feel these are the most important things.

Maguwi — continue, keep going; ochre on linen, by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

I really honour what you do, and the way that it seems everybody that works with foraged pigments, the majority of them, are about that. I’ve only come across a tiny few that are not working with honour, understanding or respect. I don't think you come to this practice without care because it's not an easy thing to work with earth pigment. There's nothing fast about it. It's very slow and I don't think you can work with it without starting to ask deep questions and to have an understanding of what it is you're working with and where it may have come from and who it belongs to and what sequence, stories & knowledge it holds.

I know where I’d like to direct the Ground Bright 22% donation. There’s someone that I have facilitated with and have deep respect for: Ella Bancroft is a proud Bundjalung First Nations woman. Her organization, The Returning, does incredible work for First Nations peoples. It's about land stewardship and a returning back to culture. It's a not-for-profit organization and she is such a powerful voice and an extremely amazing human that offers so much out into the world.

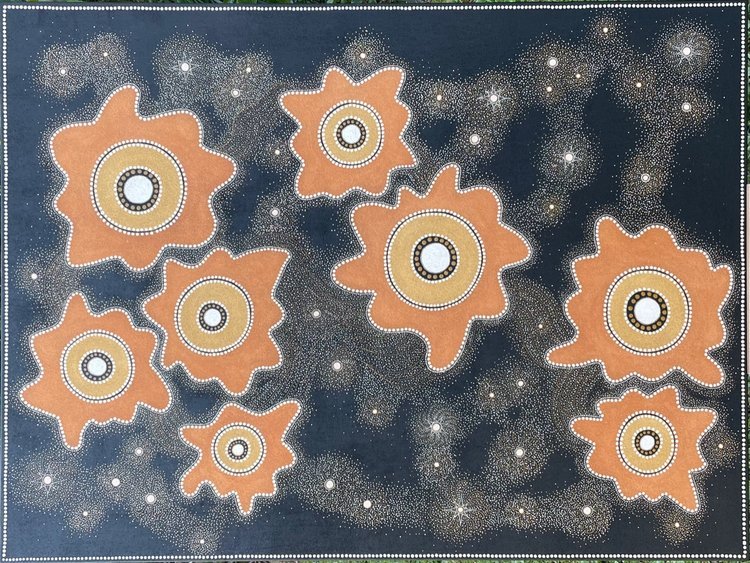

Gabuny, — shooting star, by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

(later, in another voice message…)

Good morning, Til!

I'm in the last day of packing and cramming two weeks’ worth of work into a couple of hours before we head off to Arnhem Land. And I apologize for the noise — I'm sitting outside as my family are still asleep. It's just been so huge the last few weeks on top of flood relief, on top of family health, <laugh> on top of my son, moving away for three months to do a snow season and finishing his semester and blah, blah, blah. It goes on. How are you love?

It sounds like your new projects are really exciting […]. And yeah, it sounds like the weather's been very weird there for you as well. The whole seasons seem to be a little bit mixed up and thankfully it has not rained here in the Shire much at all for a pleasant change. We’ve just had some really, really crazy winds which have been really good for drying. My head is a little scattered, as you can imagine, trying to tie in all of the different things that I've got my fingers in, like yourself, & like most of us. I'm just so incredibly excited to go to Arnhem Land, it’s somewhere where most of our mob don't have the ability or capability to see and visit. Just getting there is quite expensive & being low socioeconomic peoples, we don't have a chance to travel and see other parts of our nations around Australia. I’m also traveling with a very special friend, a traditional owner of the land that I currently reside on, Arakwal Bundjalung land. Delta also does incredible work sharing her knowledge in this highly tourist area as well as educating the local peoples, schools, business owners on this incredible land on the most Eastern tip of so-called Australia.

So, we're feeling completely honoured that we get to work with Yolngu elders and have the privilege to sit, listen, share and learn from one of the oldest continuing cultures on the planet. We will be working as mentors with Culture College and are ready to dive deep and immerse ourselves and be of service.

Tingali — good hunting ground; ochre on linen, by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

Lots has come up about protocols [lately]. It's been just little things from other people in the community and here in Australia that have popped up. And I guess it's always there, […] but, you know, everybody has such opinions. And, I don't know, it's so hard to sit on the fence. I really believe the work that you are doing, that Heidi [Gustafson]’s doing, that Melonie [Ancheta]’s doing is really, really important work. And as you know, we use our earth and our minerals every single day to live. Every time we turn on a light, the devices we use, the foods we eat, the packaging we create. It's just, it's every single day we're using earth minerals, earth pigments, earth, the natural world. And I think the work that you do is bringing awareness to that and it has such a capacity to teach.

Protocols can be really tricky — like, just me speaking to you and sharing things with you can upset some people. I do understand for some it comes from trauma, from fear but if we continue to revisit that cycle, we remain in that system, we are disconnected. There is so much to learn, so much knowledge, so much research to do and it’s time to open up and explore, share, engage and to help each other heal our past through this deep knowledge. I feel pigment and all its ancient wisdom holds some of that capacity to connect and heal.

I do understand the issues you face when asking those more difficult questions about selling pigment [through Ground Bright]. It is for me the same, because I make paintings that sell for a shit-ton of money, even though I don't get that shit-ton of money.

If you calculate the foraging, the processing, the making of a piece and for me the purchasing of expensive linen canvas then the finishing off with gallery-required taping and hanging accessories, the 50% or less leaves you with about $2 per hour. ;-) I cannot produce a lot of art, it’s really slow curating. Sometimes I feel completely disconnected with the selling of art at high prices where most of my people (myself included) and a large part of the population simply cannot afford to buy fine art.

Personally, I don't sit well with plastics. That's why I use the ochres, but it also goes much, much deeper as you know, as I've shared with you before. The selling of art is still an uncomfortable place for me but the joy I witness it gives steers me towards continuing to share. I also feel I don't have a choice as it’s guidance I’m receiving that channels through me — it’s not my expression but something much deeper. I’m not sure how my paintings are received. It seems once they are out there in the world sold, they are gone, hopefully to be enjoyed and to continue to share stories of our ancient culture and to invoke questions that bring a deeper understanding of our wealth of knowledge from this land. I think we're all still learning [and there’s still] so much to learn and navigate. And I really think what you're doing is beautiful Tilke, so thank you for doing the work you're doing and also the questions that are arising while you're in the work. It's all part of the process.

Waringgir; ochre on linen, by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

I guess at the forefront, for me, is my culture and protocols and to respect my elders and my ancestors. And I guess that's why it can be really hard, but also, I also see that there's a tightness around it and I understand why because of our history, in sharing things and in sharing knowledge. I feel there's a lot to learn out of sharing knowledge. And if we stay stuck in that restricted tightness, we don't have room to grow together as human beings. So, I'm being brave. <laugh> Maybe silly, some say.

Each different language or clan group around Australia has such a different and intrinsic connection & relationship to ochre. To all and every part of country. I will share with you one very short story. It's not actually the story, but it's just a brief recap of it because it's not mine to share [the whole thing].

There was a fella, and he took some water from a sacred spring without permission on the coast and went to inland, went far, far inland, it was desert country. He spilled one drop of that sacred water on the dry cracked earth and within the next 24 hours, a huge, huge flood occurred and wiped out a lot of people, animals, a lot of bush. It was angry water, wiping many out in its path, all food and clean water was lost and contaminated. The land was out of balance, it had something foreign upon it, something without permission or ceremony, it became sick country.

Our people tread so very lightly upon these lands and there is absolutely no separation, all is connected. Great care is taken when working with these old pigments, deep respect, connection to the lands they’re from and constant questions as to what is appropriate, what is on offer and what must remain.

There are so many sacred ochre pits throughout Australia. These were used for 1000’s of years and traded upon in a reciprocal way. These areas need to be protected, they are powerful and can become dangerous if disturbed or used inappropriately. It is so important for the land to hold these sacred spaces as for everyone to acknowledge them as our cultural heritage.

When I am not guided by my elders and educators I go back to the everyday, the disturbed, the waste, the off-cuts — the areas that are opening and gifting as you've shared in your practice and not to the completely sacred special spaces. I am also in communication with fellow pigment practitioner Yorta Yorta woman Lorraine Brigdale. We feel a kinship on sharing and deep respect for pigments. I adore Lorraine’s works, her connection to culture and her continued sharing and education via her art practise.

Purumay — west wind; ochre on linen, by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

I also really admire the strong deadly work of Sarah Hudson, Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe and Ngāti Pūkeko artist, researcher. Her deep dive into ochres, research, reclamation and the collective is a direction I would love to travel on with our many ochres.

Your life’s practice has also been on that trajectory it seems, Tilke. I honour that and the beautiful work that you do. It is not always easy and can be difficult most of the time. The more we learn into the vulnerability the more questions arise, I honour that, thank you for all that you do.

I feel in my 50th lap it is time to be brave, to share more openly and to try and lean into the vulnerability and the uncomfortableness and acknowledge that I've been chosen to share some of this information and wisdom and especially to my people in the way of holding our ochre workshops, working in communities, education etc, because when I do there is something so beautifully powerful about witnessing what happens when we have our hands in earth in its many different forms.

We (humans) export and take from the earth every day. So many natural resources, and it is not in a reciprocal way. So the small pieces that are used for education or used for a sharing of culture and a sharing of knowledge, I think completely outweighs the way that we rape and pillage our mother earth. We need more ways to give back, to balance all that is taken from her and more education of what is under our feet…

(In response to my suggestion that we invite Ground Bright subscribers to mail the Gayuli back to Mel, to be returned to the land: )

I think that's a really gorgeous idea. If people would like to send back [the Gayuli] that could be a space… I'd be open to receiving little packages and the Gayuli can come back here, and it can come back to be on Bundjalung land, it can return to country. So, like you say, some may not, some will, and then let's just see. I think by introducing that question or that opportunity, it will make people think even more about where the land comes from and how they may use that in their art practice and what it means to them and to acknowledge how powerful it is and the journeys it's taken.

Yeah, so I'm completely open to that, love. Huge exhale. <laugh> I'm so looking forward to witnessing your solo exhibition, and I hope I get to see it, and I hope someone videos it and that you can document it somehow, because I'm really interested. I'm excited to witness all the other earth pigment practitioners in the exhibition and thank you for the opportunity to exhibit there. And we'll see <laugh> who knows. Lots, lots is an unknown at the moment, but right now I'm stepping away from flood relief. I'm stepping away from family and all the messiness that that entails and work, and responsibilities and diving deep into just being open and surrendering to learning and listening from completely different traditional peoples from my homelands in the top end of this ancient continent.

I understand where all of these unknowns and feelings are coming from. And I guess we're still in the infancy of this type of learning and sharing through these ancient things that are earth pigments. Sending you lots of love, Tilke, and go gently.

~ Melissa Ladkin, February ~ July 2022

Detail of ‘Kama’ by Melissa Ladkin. Image courtesy of Melissa Ladkin.

until next time, friends

We’re in the infancy of this type of learning and sharing about earth pigments — Mel’s words are important reminders. Our relationships are in a state of evolution, and I’m excited and ready to be part of their change and growth — however that looks.

I hope this reading has deepened your sense of connection to the planet, or, perhaps, if you’re a pigment practitioner or artist, to your practice.

Much more to share with you along these lines, from my own studio goings-on, in next month’s newsletter.

If any of this has moved you to drop me or Mel a line, please do write to us at info@wildpigmentproject.org. We’ve love to hear where you are in this process.

To subscribe to Ground Bright, please go here.

Stay Brave,

<3 Tilke