pied midden: issue no.34 : records of being held: tilke elkins

Three years of Ground Bright: leaves and clay marbles, by Tilke Elkins. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

lazy summer emotional processing

This newsletter is late.

It’s late because I took the backroads to Vermont…from Oregon. It’s late because when I got to Vermont I spent the better part of three weeks not typing talking zooming reading posting liking thinking researching grinding levigating mulling painting cleaning arranging photographing pontificating…. as I do most of the time. Instead, I played Chinese checkers with my parents. I’ll just say “playing Chinese checkers*” here as a sort of metaphor for what we were actually doing. We did play the actual game at least once a day, it’s true. It’s a great game, perfect for three people. We’ve played it together many many times in the course of my life, and for me it’s always been a fairly boring process of watching my mom utterly cream me and my dad. This time, though, instead of playing distractedly, I decided to really play. I focused. I gracefully accepted — even invited — my mom’s coaching (don’t laugh — you’d be surprised what a subtle game this can be!). I worked to dissolve what was grumpy and resistant and defensive in me and replace it with humility, curiosity and an openness to learning. Powerful things began to happen to the dynamics between me and my parents. We talked (where “talked” is shorthand for a variety of vocal utterances, not all of them sedate.) We smashed up old patterns and designed the delicate architecture of new ones. We met each other again, as who we are now.

On our way from the west to the east, my partner Noelle Guetti and I stopped to visit an old friend in the north woods, a friend I’d grown distant from in the several years since our active friendship had petered out. We took a walk, and I said the hard things that were lodged in my heart. I asked — urged, really — my friend to be honest with me about why she’d pulled away, and when she told me I listened. I said what I understood about hurtful things I’d done and said in the past. She did the same. We cried together in the misty rain, eating wet blueberries off the wild bushes lush from bear dung. And for the first time in years, we had a sense of possibility, that we might begin to trust each other again. I was impressed and proud of us in that moment. Impressed that we had moved towards the hard conversation, instead of shuffling away from it. As we made our way back to her cabin, where her baby waited for breastmilk, I realized that in the time since we’d been close, when neither of us was particularly good at talking about hard things, we had both independently been working to dismantle the internalized racism we grew up with — she through her work as a midwife, and me through this project. And that had something —significant, I think — to do with our ability to show up for each other now.

A longing to hear what may hurt opens invisible doors to entirely different ways of being. To have the urge to sit in the terror of being wrong, or of confessing the ache of the need to be loved and belong: it’s a horrible urge, it’s uncomfortable, wrenching, chaotic — but it may be the only impulse that can repair what’s been broken or destroyed. Anti-racism work, decolonization work, in turns out, builds up that curiosity to hear what’s hard, a courage that if you’re lucky will extend to every relationship in your life: friends, lovers, parents, siblings, as well as all the important strangers you affect with your presence and words. And when two (or three…) people who share the courage to ask hard questions come together…well, the unexpected can happen.

* Chinese checkers is not, nor ever was, as you may have guessed, Chinese. It’s a German game called ‘Star-Halma,’ based on an American game called ‘Halma,’ renamed ‘Chinese Checkers’ as part of a dubious American marketing scheme in 1928.

Paint-brush-cleaning leaves, Tilke Elkins. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

As I prepare for the up-coming exhibition series opening at form & concept next month, where 27 artists who have contributed pigment to Ground Bright will exhibit work and pigment sets, and I’ll also have a solo show of my own work with pigments, the longing to hear what may hurt feels extra-vulnerable, as well as extra-exciting. I’m sort of buzzing with it. How will my hard-question-asking land in the context of a gallery show in Santa Fe, a rich city in the state with the third-highest poverty rate, with so many layers of indigenous and colonizer histories? The familiar questions now ripple over me in prismatic anticipation. Especially this one: what does it mean that the focus I’ve been able to give this project — working intensely on it for the past three years — has been made possible through the proceeds of the Ground Bright subscriptions? That it pays my bills and gives me a living? Yes, together we’ve directed more than 25K to to organizations I deeply admire and want to support. That’s a sum that would have felt utterly unreachable to me as an artist living without a bank balance for years, and that feels good. It feels good to give other artists the chance to direct money to organizations close to their hearts, too. But, what about the fact that however you look at it, money is being exchanged for earth? Not to mention that the project has been so successful because people are naturally drawn to direct their hard-earned cash to organizations they believe in, especially when there’s a pigment treat in it for them too. Put crassly — or, let’s say, directly — am I just using these organizations for my own gain? While selling the body of earth for a profit? Is the whole Ground Bright endeavor just a well-dressed form of extraction, exploitation and appropriation?

My strategy aims for win-win. If I benefit, how can others benefit? If I take from the earth, can I do it with love and care in a context that gives back? If I benefit from mentioning someone else, can I really send that benefit back to them in a substantial way, backing talk with money? Ground Bright functions within capitalism, a system that is ultimately exploitative and reliant on inequity. Is what we’re all doing together here with this — subscribers, pigment contributors, artists and fans included — using the existing system as a sort of bridge towards a different way of being — one focused on equity, on connection and relationship, on stewardship? Or are we just perpetuating that which we deep down know is wrong, in a format that looks benevolent?

I can say with certainty that this project has brought good to many people. I would dishonor the incredible, generous and loving efforts of so many if I didn’t shout that from the mountains. It’s changed us, it’s helped grow us, and most importantly, it’s connected us. That doesn’t mean that it should continue forever in its current form, and it doesn’t mean that everything about it is at the level of integrity it needs to be at. It isn’t time to stop asking hard questions, and I invite you, as always, to continue to join me in asking them.

But it is a time, with this upcoming Group WPP exhibition, to celebrate that which exists, to celebrate the work we’ve done and are continuing to deepen and grow, even if parts of what we do are still broken. It’s a time to appreciate these dusts that have formed the shape of our lives: to thank them, to praise them, and to listen to what will come of this togetherness.

Underlog-in-the-middle. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

underlog

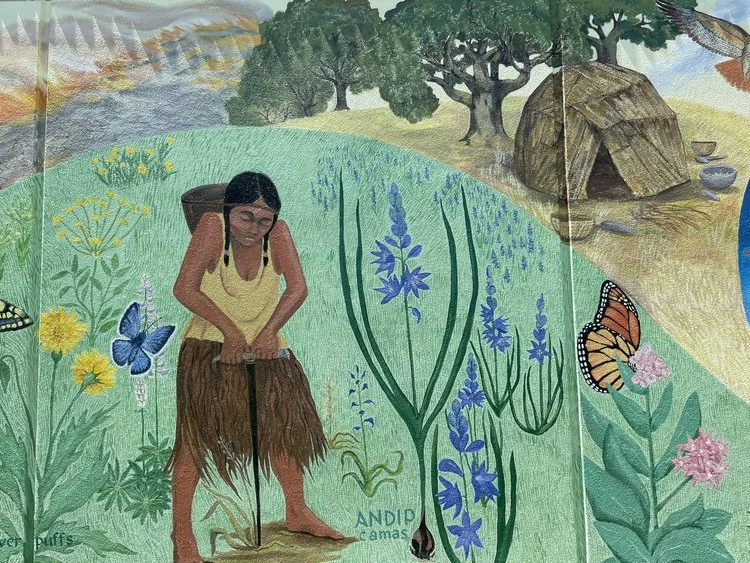

I’m the pigment contributor this month, and my pigment, which I call Underlog, comes from Kalapuya lands in Oregon where I’ve been a guest since 2001. This deep brown earth pigment, found when wind pulled down a large fir in a storm, feels very much connected to my involvement in recent efforts by the Kommema Kalapuya community to educate the people of so-called Oregon about Kalapuya history, and to nourish a current land rematriation project on Kommema Kalapuya ancestral homelands in the southern Willamette Valley. The first time I really worked with Underlog was this spring, when I was invited to help paint a mural depicting Kalapuya elder Esther Stutzman telling the stories of her ancestral lifeways and relationships with plants to a group of rapt listeners. Artist Susan Applegate designed the mural together with Esther Stutzman. The two women have been friends for years. I was lucky to hear their story once when I visited them in Yoncalla.

They met in the 80s and realized their ancestors had had a unique relationship. In the 19th century, Ester’s many-greats grandfather, Chief Halo, also known as Camafeema, invited Susan Applegate’s ancestors, the Applegate Brothers, to settle in the area, describing them as “skookum,” which I took to mean something like what I’d call “good-in-their-souls” or “friendly.” The brothers moved to the area and Chief Halo told them where they should build their house — which remains in the Applegate family today. In the mid 1800s, when the US government rounded up all the Kalapuyans and marched them on a trail of tears to a concentration camp-like reservation, the Applegates insisted that Chief Halo and his family remain. Today, Esther and Susan live a few paces from each other on Kalapuya/Applegate lands and are close friends who have both, in their separate but overlapping ways, dedicated their lives to recording and sharing their family histories through story and painting.

Section of mural designed by Susan Applegate in consultation with Esther Stutzman. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

Ok, so — I was helping Susan do a little bit of painting on this incredible 60 foot mural, a project funded by a local group, Beyond Toxics, and of course I was thinking, what if we could do a section with pigments from the land? I ran this by Susan, and she helped me narrow it down to a frieze of patterns drawn from hats worn by the ancestors. The pigment that was to become Underlog came to mind, and I did some tests with it and three other earth pigments from nearby. My stomach dropped a little as I mixed the pigments into polyurethane, but it also felt right. That’s what this called for, and it’s something I’d been wanting to explore for a while: a way to share mineral pigments in public spaces in the material language (acrylic paint!) of those spaces. It worked amazingly well.

Frieze painted with Underlog, yellow ochre, and Whilamut pigments. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

At the dedication ceremony for the mural, Dr. David Lewis, Kalapuyan historian and assistant professor at Oregon State University, spoke of the mural’s significance. He stressed how overdue it was, and how disturbing it was that there was so little visible Kalapuya presence in Oregon today. He recalled a visit to Australia and New Zealand / Aotearoa, where he observed that the First Nations cultures there, though severely damaged by colonizers, were still so much more intact and visible than in Oregon and the greater US. Dr. Lewis has done huge amounts of research work to preserve Kalapuyan history, much of which he publishes online in his exhaustive blog, Quartux, the Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology. I highly recommend visiting the blog, which draws from thousands of archived documents from collections all over the continent. Between them, through years of very hard work, Dr. Lewis and Esther Stutzman have played a significant role in ensuring that Kalapuya culture and history will not be lost.

Underlog, gathered with Esther’s approval of the Ground Bright process, is a tribute to these efforts toward cultural revival. The 22% will go to another crucial endeavor: the Cha Tumenma Land Project, led by Esther and her descendants. It’s a land rematriation project on over 200 acres in their traditional territory. Cha Tumenma, or “place of ancestors,” will be a permanent place for the Native summer youth camps they’ve been running for decades. It’ll have a community garden, and a place to practice cultural fire and on-site sustainable forestry. They’ve met their goal but their campaign is still running. To donate directly, go here.

Stack of shadow records for ‘After Shadows.’ Photo by Tilke Elkins.

i interview myself

WPP: Tilke, this year you’ve been both curating a group WPP exhibition and preparing for a concurrent solo show in the same gallery. Can you tell us a bit about this exhibition series? How did it come to be? I thought you told me once that you didn’t really dig the gallery scene and felt uncomfortable about showing your work in a white box!

TSE: Yeah, you’re right, I think I did say something like that. I think a lot of artists feel that way. But that was before Noelle and I wandered into form & concept in 2017 or so and met director Jordan Eddy. Jordan is a total art saint! He’s a brilliant director, who has brought artists doing really potent stuff in realms of social and environmental justice into the gallery. He’s also a brilliant writer. He just wrote an amazing article, How a Group of Navajo Teens Promoted a Re-Telling of History, published in the art mag, Hyperallergic, that documents how a letter from Diné high school kids led to the construction of a permanent exhibition at Bosque Redondo Memorial in New Mexico.

Anyway, Jordan, who coincidentally grew up in the town where Noelle and I live, was really interested in Wild Pigment Project and my own work, and I think had a vision early on that a joint exhibition might be just the thing. His encouragement gave me the fuel I needed to bring it all together. Then he saw Noelle’s incredible weavings, and gave her a lot of inspirational fire too.

WPP: Yeah, I agree, Jordan is a delightful and stupendous person. He drove work for the show all the way across the desert from Eugene to Santa Fe in a big truck himself, while you were lying around playing checkers in Vermont! Amazingly generous. So, can you tell us a little about this group show? Who’s in it and what’s it all about? Was it hard choosing the artists?

Earth pigments gathered by artist Heidi Gustafson in preparation for work in the WPP show. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

TSE: Ah, I like that last question. The answer is, no, it wasn’t hard choosing them at all because all 27 are artists I’ve worked closely with, interviewed, and spent time getting to know. They’re all artists who have contributed a foraged pigment (or three!) to Ground Bright since 2019.

To give you a feel for the show, I’ll stick the official description in right here:

Wild Pigment Project Group Exhibition

Since 2019, Wild Pigment Project has been a nexus point for the burgeoning global wild pigment movement. Bringing together painters and dyers, ink-makers and ceramicists, researchers, scientists and traditional cultural practitioners to explore pigments found in plants, minerals, and the industrial waste stream, Wild Pigment Project is dedicated to fostering difficult conversations about land and cultural histories by exploring what it means to forage for art materials in the era of climate catastrophe and renewed confrontation of colonial racism and cultural genocide.

For the first time, the artists who have made this project possible will be exhibited together in a show featuring their work alongside pigment sets that reflect each artist’s unique collaboration with foraged and hand-prepared materials. This is a rare opportunity to experience not just the dynamic range of expression possible through these wild pigments, in painting, textiles, printmaking, ceramics and sculpture, but also the ‘behind-the-scenes’ workings of the pigment-centric studios, fields, forests, vacant lots, kitchens and backyards where these works are produced.

All artists in the show are contributors to ‘Ground Bright,’ the monthly pigment subscription that supports Wild Pigment Project and generates monthly funding for land and cultural stewardship organizations. Through Ground Bright, the project has raised over 25K in reciprocal offerings to land and community organizations, and reached more than 2K subscribers in 17 countries. The project, with an Instagram following of 44K, also provides an international listing of pigment artist/educators, through the Pigment People Directory, offers Reciprocal Guidelines for working with wild pigments, hosts an online gallery, and generates regular funding for educational support for artists in global pigment study.

The exhibit is the result of countless hours of dialog between the pigment practitioners represented and artist Tilke Elkins, who founded the project and runs it solo, with support from her partner, Noelle Guetti, who fulfills the Ground Bright subscriptions each month. Tilke has formed lasting friendships and conducted extensive interviews with many of the contributing artists about their complex relationships with their foraging places for the project’s newsletter, Pied Midden. These interviews reflect the enormous spectrum of collaboration with pigments currently taking place on the planet, and the emotional, cultural, political and ecological intricacies implicit in the act of bending down and scooping up the body of the land itself.

Tilke is extremely honored and grateful to the artists for their kind, generous and heart-felt participation in this project, and is humbled to act as curator for this momentous coming-together of beings — human, elemental, botanical and mineral.

Tilke Elkins and form & concept will join in donating 11% of the proceeds from this exhibit to IAIA.

Featured artists: Melonie Ancheta, Heidi Gustafson, Thomas Little, Natalie Stopka, Caroline Ross, Amanda Brazier, Karma Barnes, Nancy Pobanz, Hosanna White, Britt Boles, Iris Sullivan Dare, Lorraine Brigdale, Julie Beeler, Nina Elder, Lucille Junkere, Scott Sutton, Sydney Matrisciano, Marjorie Morgan, Joshua Ruder, Catalina Christensen, Adam Blaustein Rejto, Daniela Naomi Molnar, Caitlin Ffrench, Teri Power, Melissa Ladkin, Sarah Hudson, Stella Maria Baer.

Desert pigment set by Nancy Pobanz. Image courtesy of Nancy Pobanz.

WPP: Well, that’s pretty exciting. I can’t wait to see them all together in one place, with their pigment sets displayed alongside their actual work! And I hear you have a solo show happening at the same time in a different part of the gallery. What’s that all about? How do you feel about it? And you and Noelle have collaborated for this too, right?

TSE: How I feel: I feel pretty excited & grateful for this opportunity to share my work, because I’m not an artist who’s exhibited that much. And, I’m a little embarrassed to have a solo show while all the other WPP artists — many of whom should have the whole place to themselves — are sharing their space together. It feels…. a little unequal. Also it actually isn’t a solo show, because it features textile work by Noelle.

My show is called Records of Being Held, and the title refers to a myriad things. It’s about being held by the land, about holding the land as pigments-in-hand, and also about the land being held, as in held captive. Everything in the show express these, and other versions of record-keeping and holding, recording and being held.

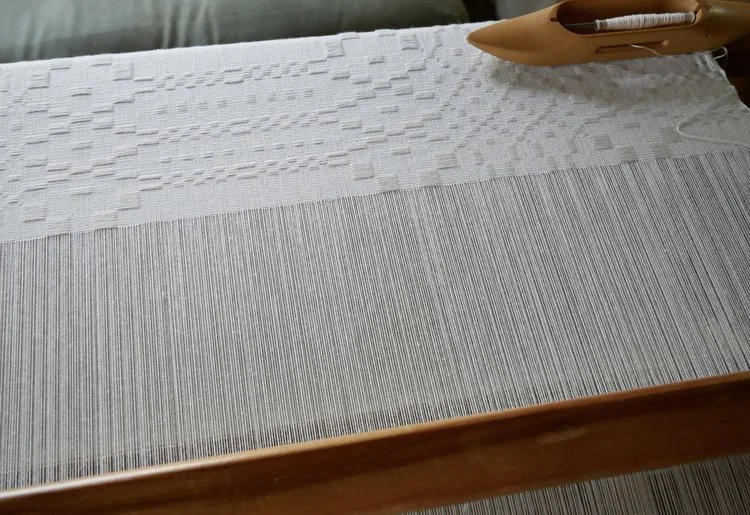

The largest ‘piece’ is three double-sided paintings (so, six paintings) in pigment, on plywood. Noelle has a significant textile contribution in this piece: a large, stunning, intricately patterned woven white cloth, that will be used to wash the pigments off the cloth. It’s our first significant studio collaboration, and we’re excited to embark on many more together. I’m totally blown away by her work and am hugely honored to include her piece in this.

Here’s the official description…it’s long, so don’t worry if you don’t wanna read it all right now! Clip and save for when you visit the show online or in person.

Detail from ‘Nothing Gold Can Stay by Tilke Elkins. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

Records of Being Held

Records of Being Held is a series of six personal memories of place temporarily held in foraged mineral pigments with occasional egg and cherry gum binder on three sheets of plywood recovered from constructions sites in the Eugene/Springfield region of so-called Oregon.

Paint, as a living and energetic collaborator, and as an embodiment of the soil, rocks and plants that make up the places that hold me, works with me to leave a record of my experience of bodily and sensory intimacy with that place. These records, which communicate to the full sensorium through their materiality, render the way that eyes carried by a body in constant motion and motivated by sensory exploration register the memory of place.

The pigments themselves are in flux, in motion, each carrying a unique geological history and chemical presence, as evidenced by their range of colors, textures, scents, and even the sounds they produce when crushed or stroked. As occupants of the surface layers of the ground, these mineral and botanical pigments are witnesses to the life histories that have passed over them, many thousands of years of multispecies relationships and human histories of both caring for landscapes and disregarding them.

These large painted records are intended as evidence of my physical intimacy with specific places, rather than as representations that act as windows into sublime landscapes. Countering the tradition of “capturing” a landscape through the formal distillation of its visual beauty, these records are instead offered as temporary collaborative performances with materials, conjunctions that will dissolve and evolve. After a contractually agreed upon term, the paint will be washed off by me and other members of the pigment community using ceremonial cloths woven by textile artist Noelle Guetti. The pigments will be gathered up to be further engaged through future performances, and eventually ritually returned to the sites where they were collected. Although these paintings will be offered for purchase, for an initial sale price, the pigments themselves will be available for “rent” only, with an annual fee paid at the time of the initial purchase to the Kommema Cultural Protection Association, an organization led by Kalapuya elder Esther Stutzman, currently rematriating an area of ancestral Kalapuya lands in the region where these pigments were gathered. One exception, Family, composed of 47 Ground Bright pigments, will direct all “rent’’ monies to the Wild Pigment Project Equitable Opportunity Fund, and the reclaimed pigment will be sold through the project to raise additional funds for this purpose. The plywood boards, made from trees grown near these sites, and intercepted from the waste stream, will remain in possession of the buyer as palimpsests of their participation in this record-keeping, along with the woven cloths, once their pigment-returning functions are complete.

Pigment-reclamation cloth by Noelle Guetti on the loom. Image courtesy of Noelle Guetti.

The pigment-reclamation cloth is woven by my partner and collaborator, artist Noelle Guetti, and stitched to form a single canvas that must be cut each time a painting is sold/rented. The cloths reflect patterns used by early weavers of sail and artist’s canvas, and are designed to show places where the pattern is dissolving or being worn away. Canvas, integral to the infrastructure of the colonization of the so-called “New World” and the subsequent visual records of “exotic” landscapes, is, through this process, inverted from a surface which holds the landscape captive to a vehicle of return which carries the pigment back to its land of origin. The cutting of the canvas/sail represents a ritual dismantling of colonizing structures.

Individuals interested in participating in this painted performance engage the materials by offering financial support for communities in ancestral relationship with the land where I found the pigments. Instead of exchanging money for ownership, ‘collectors’ become collaborators, enacting these further pigment futures by stepping into relationship with the pigments themselves, their landscapes, their ancestral custodians, and their multispecies communities, as well as with form & concept gallery, me, the artist, and the larger pigment community.

A note about Kalapuya ancestral pigment practices:

Ancestral knowledge of Kommema Kalapuya mineral pigment use was destroyed through cultural genocide, says elder Esther Stutzman. Kalapuya cultural objects are primary plant-based, she explains, so most colorants were likely to have been botanical, but, she says, it’s also quite possible that ochres were used for the ornamentation of baskets and other weavings. There is a small number of ancient Kalapuyan pictographs made with ochres, as well as one made using green earth.

Detail from ‘Parents’ by Tilke Elkins. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

About the visual language of the series:

As a lonely child of busy parents, I sought solace in two things: Saturday morning cartoons and my rambles in fields and woods. In the first I found a noisy, peopled, technicolored world built by hand through imagination and creative freedom, which punctuated the grey stillness of the quiet, early-morning house. In the second, I found the listening ears and reassuring presence of the interspecies community, a living playground that engaged my body and my longing for companionship.

Looking at art was a bonding activity for my family, and in the many museums we visited together, I found my gaze predictably drawn to the scenes behind the figures: the tiny landscapes in Da Vinci’s blue distances, the cones of hay on the outskirts of Breugle’s villages, the strange twisted trees in Bosch’s paradise. I wanted the trees and the boulders to be more than just backgrounds, to be featured as personalities, capable of dialog and participation, instead of mute support for humans. I wished that these aspects of the scene were the painters’ central subjects rendered life-sized, ready to offer themselves to me to step into as I did on my solitary rambles. Saturday morning cartoons taught me that animation — the act of bringing drawings to life — could convey personality regardless of form. The culture that raised me also taught me that these two things I loved — the wonders of animation, and the experience of communicating with the interspecies community — were activities reserved for children, and not of “the real world.”

The impulse to validate both imaginative drawing and a communicative relationship with the interspecies world as crucial adult activities drives this series. Records of Being Held is designed to substantiate the presence of the living world and its many forms as not just “actants” — beings capable of playing imaginary roles — but “interactants”: beings with agency capable of interaction and collaboration.

Tarweed shadows. Photo by Tilke Elkins.

The above image is from another piece in the show, called After Shadows, but the description is too long to include in this newsletter, and besides, I should leave a little mystery for show time. Here’s the briefest excerpt from the description:

After Shadows is a long-term project that has been many years in preparation, and is still in its early stages.

The project involves a registering of plant shadows as they are cast by the sun on stone cliff-faces in remote areas unlikely to be disturbed, in a variety of ecosystems on the planet, thus serving as deep-time records of the plants that represent botanical life today.

Noelle Guetti will also feature another of her works in this show: the first in a series she’s calling Field Clothes. The After Shadows garment is a one-piece coverall made with nettle and green-clay-dyed yarn and designed to hold paint brushes and paint pots, which Elkins will wear for the next stage of this piece, the on-site botanical cliff paintings.

Just wait ‘til you see the coverall! It’s pretty much my dream garment. Noelle somehow manages what’s extremely rare in the contemporary age: she can dye, weave, design AND sew stunning original garments, and she’s absurdly modest about it all.

WPP: Oh, I hope you wear your Field Clothes to the exhibition opening…

TSE: I so will.

(end interview)

gotta run

Thanks so much, dear reader, if you’ve made it this far! Noelle and I can’t wait to see you — those of you who can make it! — at the gallery opening on September 30th. We’ll be hosting a virtual opening too, TBA. Please come and shine sparkles on all the fabulous artists in the show, and meet each other, and do PIGMENT PARTY extraordinaire with us.

We’re also planning a story-sharing event for sometime during the shows, which run September 17th (soft opening) to December 3rd. More on that soon. Also, I’ll be doing wee mini features on all 27 artists in the WPP insta feed starting soon, so find us there if you want more sneak previews.

I shut up now!

Send me your hard questions. And…

Stay With Us,

<3 Tilke

Family Portrait. Photo by Tilke Elkins.