pied midden: issue no 13 : finding blue: coastal valley collaboration

Originally published August 8, 2020

singing it in

I was recently invited to present my work with Wild Pigment Project at a very sweet online event: the Feedback Friday live video blog and chat, hosted weekly by Kathy Hattori and Amy DuFault of Botanical Colors, a natural dye studio based in Seattle. Since the start of the pandemic, Kathy and Amy have been gathering people (quite big crowds, actually!) to Zoom together and learn from (mostly) natural dyers. It’s an extremely cozy community of artists who ask excellent questions and delight in the kinship of sharing dye experiences, especially in this time of isolation. And Amy does some great intro singing to get it all started! Highly recommended: every Friday at 9 am west coast, noon east coast.

Before I presented a whole ton of slides about pigments & ethical foraging & land stewardship & accidentally-stumbling-onto-an-obscure-formula-for-prussian-blue ( that happened! ) AND how to makes lakes ( ok, there were a LOT of slides…but I had to show these dyers that they can make paint with their spent dye baths !) … I read a thing that I wrote. What I wrote came out of rich conversations with my pigment mentor, Melonie Ancheta, about meaning and art, and reflections I’ve had since listening to a recent interview with the brilliant and wise Heidi Gustafson, on the Knitted Heart podcast ( if I were allowed to boss you around, dear reader, I would tell you that you MUST listen to this interview! ).

Heidi communicates essential messages about the relationship between humans and matter, and explains how this relationship can be a subtle form of sensual, embodied activism that allows for deep healing, especially between the land and people whose ancestors have historically harmed and disrespected the land. Heidi’s words so often feel like distillations of everything my heart most wants to express, and they’re woven into what I wrote. Thank you, thank you Melonie & Heidi.

A few people asked to see the writing afterwards, and I thought this might be the best place to share it. So here it is, with some very minor revisions:

I’m part of a culture — White, Western, settler-colonizer, Euro-American culture — that has, for many hundreds of years, shamed and punished anyone who behaved as though all is connected and alive.

It’s a culture that has severed spirit from matter, and this severance is the origin of capitalism as we know it. It’s what’s allowed many humans to treat the whole planet and everyone on it as though they’re there to be extracted and used. Instead of relating to matter as life and asking, “What’s my relationship with this being?” White culture, capitalist culture asks, “What can I get out of this? or, “How can it serve me?”

Two recent Feedback Friday guests — both of them artists working with indigo, incidentally! — gave their own, different cultural perspectives. Kibibi Ajankou talked about, “Bringing the meaning into the material,” and asking, “What is the work we must do?” Aboubakar Fofana pointed out that in West African culture, there is much more to working with a plant than its “outcome.” Blue dye may be an “outcome” of the indigo plant, for example, but the relationship between people and the plant is about so much more: medicine, protection, guidance between the earthly and the divine, to name a few aspects. The plant gives its spirit to offer these things, Aboubakar points out.

Global warming, the pandemic, and the Black Lives Matter movement have brought into focus, for people raised in a capitalist culture, a longing for meaningful relationship with matter, joined by the awareness that real relationship with the land means going deep into dialog, on a spirit level, with the land itself, about the pain and damage that the culture of white supremacy has brought.

Many white people feel so far removed from a culture of origin that isn’t extractive and severing that looking for these roots feels impossible. But for many on this continent, the powerful presence of the land has offered an entry point back into intimacy with the ever-present spirit in all lifeforms. In order for true relationship to take place here, however, we as white people can engage with the land not by appropriating the spiritual structures of other cultures, but by going deep into the damaging histories our ancestors brought here, and dialoging sincerely with the land about those histories.

Foraging for rocks and breaking them open, or, “futuring soil,” as Heidi Gustafson calls it — or, gathering plants and soaking them in steaming water to discover their pigments — are sensual, wordless dialogues with the potential to bring about meaningful, reciprocal relationships and healing. Wild pigments can act as a bridge between severed, abstract thinking — the “idea of red” — and matter-joined-to-meaning: red ochre from the mountain behind your house.

Even though I personally have a deep, complex connection to place, and have been in dialog with trees, rocks and plants since I learned to walk, I sometimes watch myself fall back on extractive language when I’m sharing my work with wild pigments with students. For anyone raised in my culture, it can be more comfortable for me to talk only about the useful qualities of a plant or a stone, than it is to be introduced to matter as an equal sentient presence, and a potential friend. But such an introduction is always the goal in my heart, and if you remember nothing else from this presentation, I invite you to remember that.

~ Tilke Elkins, for Botanical Colors feedback Friday, July 24th, 2020

a maybe not-so-lost blue

I first heard word of a pigment called ‘Maya Blue’ back in 2008. An article in the New York Times reported that some professors at Wheaten College, Illinois had taken a closer look at an artifact from a collection at Chicago’s Field Museum — an incense bowl — and decided that the method used to heat the indigo and palygoskite clay, the identified ingredients in the blue, had likely been ritually-used burning copal incense. This was news, because no one in the scientific community had yet figured out how the bond between the plant and the mineral was formed (and in fact, the nature of the bond itself remains somewhat of a a mystery to this day).

The incense theory was challenged in 2013 by a team of scientists at the University of Valencia, in Spain, who discovered that the blue contained not one but two pigments — indigo, which is blue, and dehydroindigo, which is yellow. The presence of the yellow pigment would explain the turquoise, almost greenish hue of the special blue. If I understand their research correctly, it seems the dehydroindigo forms under much hotter temperatures than those reached by burning incense. They suggest, too, that the recipe for the pigment probably developed very slowly, over time, beginning as early as 150 BCE, where other accounts place its inception at 700 CE.

Brilliant blue pigment on an ancient Mayan mural in northern Guatemala.

It is generally accepted that the knowledge of how to make ‘Maya Blue’ was “lost” for centuries, only to be rediscovered in 1963 by Constantino Reyes-Valerio, a prominent Mexican scholar of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. He’s the one credited with re-discovering the ingredients in the pigment. He also coined the term “Indochristian art” when he realized how much collaboration took place in the 1500s between Spanish colonists in the Yucatan and the Indigenous Mayan, Toltecan and Totonacan artists there. In the convents and churches, the blue robes of the madonnas, he found, were painted not with lapis lazuli, as they were in Europe, but with a different, more turquoise kind of blue. Then, as time passed, people supposedly forgot what the blue was and how to make it. His book, De Bonampak al Templo Mayor, explains what he’s learned about this era and the mysterious blue pigment, and includes his blue recipe.

Detail of a madonna in a church in Mexico, painted by Baltasar de Echave in the 1600s, using ‘Maya Blue.’ Such a quantity of lapis lazuli would likely not have been affordable! Photo credit: Museo Nationale de Arte Mexico.

When I reflect on what I’ve learned this year from Vera Keller, a history of science professor at the U of Oregon, about the apocryphal nature of pigment origin stories, I find myself wondering if the knowledge about how to make this ancient blue pigment was ever really lost. It seems much more likely that it was “lost” to certain people — namely, the people who were not related to those whose ancestors first made the pigment. I wonder.

Michel Garcia, a French master of natural dyes, is responsible for teaching everyone I know who knows how to make this blue his recipe. I’m curious where he learned it. I’m also looking forward to perhaps connecting with Raúl Pontón, a professor of natural dyes in Mexico who has spent years learning from Indigenous artists. He has suggested, I’ve heard, that traditionally, this blue was made not by heating it at all, but simply by mixing it with small amounts of limestone. This feels to me like a clue that the recipe was indeed never “lost.”So much to learn.

Blue pigment made by combining powdered indigo with palygorskite clay (or, as you’ll soon read, a number of other clays!) doesn’t fade. Pretty much every other plant-based dye or pigment will eventually vanish under the bright light of the sun, but this blue will not. This is utterly remarkable, especially in a world where everlasting blues are extremely rare and hard to find. The brilliance of this blue will far outlast blue plastic, for example. And it will keep up perfectly well with the endurance of lapis lazuli. Do you see what I mean? It’s very powerful.

Kenya Miles, and Blue Light Junction Studio. Blue Light Junction is a natural dye studio, alternative color lab, retail space, dye garden and educational facility in central Baltimore. Kenya is also artist in residence for the Baltimore Natural Dye Initiative at MICA and Parks & People, an initiative to grow and process natural dyes in Baltimore city.

This month, Ground Bright has the great pleasure to have received a contribution of blue pigment, inspired by what’s believed by some to be the recipe for ‘Maya Blue’ (I would really love to know what it was originally called!). The indigo plants — persicaria tinctoria — were grown as the result of friendships and collaboration, and a rising passion for indigo-growing and dyeing in the Pacific Northwest. The contributors — Britt Boles, Kara Gilbert, and Iris Sullivan Daire — grew the indigo plants. Britt prepared the pigment, using palygorskite-indigo clay acquired from Scott Sutton/Pigment Hunter.

Collectively, Britt, Kara and Iris are directing the 22% of proceeds from this month’s subscription proceeds to Blue Light Junction, another community collaboration, on the other side of the continent. Blue Light Junction is an education center and dye garden in Baltimore, Maryland that draws from experiences and relationships that developed during the Baltimore Natural Dye Initiative, an incredible project that took place last year. The Ground Bright donation will go towards fundraising efforts for a current Blue Light Junction buildout. To donate to the project directly, please visit the campaign here.

Britt Boles with a fresh indigo bath. Photo by Christine James.

I interviewed Britt Boles for this newsletter. I’ve learned an enormous amount about indigo from her, and I think you will too. Here’s our conversation…

WPP: Indigo is a powerful plant with a rich history of relationships with many different human cultures: a medicinal, spiritual and aesthetic collaborator. How did your path with this plant begin?

My indigo inspiration began with witnessing the work of artist Rachel Blodgett of Serpent & Bow. Her use of indigo batik adorned undergarments is striking and really encouraged me to ponder how my most intimate clothing is made and by whom and with what. The cloth that touched my body all the time, I had no connection or relationship to it. It opened up the door and let the light spill in on what was missing: connection to source. Direct raw tactile connection was something I was craving in my post-partum period after giving birth to my little, so I dove deep down the dark blue rabbit hole, many late nights nursing babe and researching indigo. A divinely timed instagram post lead me to Kara Gilbert of Vibrant Valley Farm (the major contributor to Coastal Valley Blue!). She was in her first year or growing Persicaria Tinctoria (aka Japanese Indigo) thanks to Rowland Ricketts. Kara, my indigo fairy godmother, gave me my first plants, encouraging me, sharing generously all she knew about the plants. After moving to the North Oregon coast, I met Ginger Edwards, owner of North Fork 53 Coastal Retreats and Gardens, who is a major gardening & soil and all around mentor. Thanks to their generosity, I have been growing persicaria tinctoria and other natural dyes at their farm for the past 4 seasons.

I love learning about the origins of seed and it is something I have been focused on this year while experiencing much gratitude for the work of seed keepers! Polygonum Tinctorium = Persicaria Tinctoria . The classification changed from Polygonum Tinctorium to Persicaria Tinctoria the second season I was growing and it still throws folks for a loop, but it is indeed the same plant. What I have been learning this year, thanks to the knowledge sharing of Takayuki Iishi of Awanoyoh, is that there are many varietals of the persicaria tinctoria/polygonum tinctorium plant. Over 50 varietials existed at one point in the Edo period, but now only approximately 11 are still cultivated. I am still learning about the origin names of my seeds and I currently grow 5 varietals. I am discovering that their names of origin are: Kojyoko, Senbon, Chijimba, Maruba, and Amabe. Varietals would have been specific to an area/region or even farm. The common name for Persicaria Tinctoria has been popularized as "Japanese Indigo or Chinese Indigo", but it is native to Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Korea, and Taiwan and still is continually utilized in the rich tradition of dyeing. Unfortunately, most of the seed sellers that I encounter do not always know, pass along, or keep track of the varietal origins, so a lot of folks don't know what they are growing and at this point some may have hybridized. I feel that learning the lineage and origins of seeds (and really anything) allows me to appreciate and consume in a different way. I will likely be peeling back the layers of this awareness for the rest of my life.

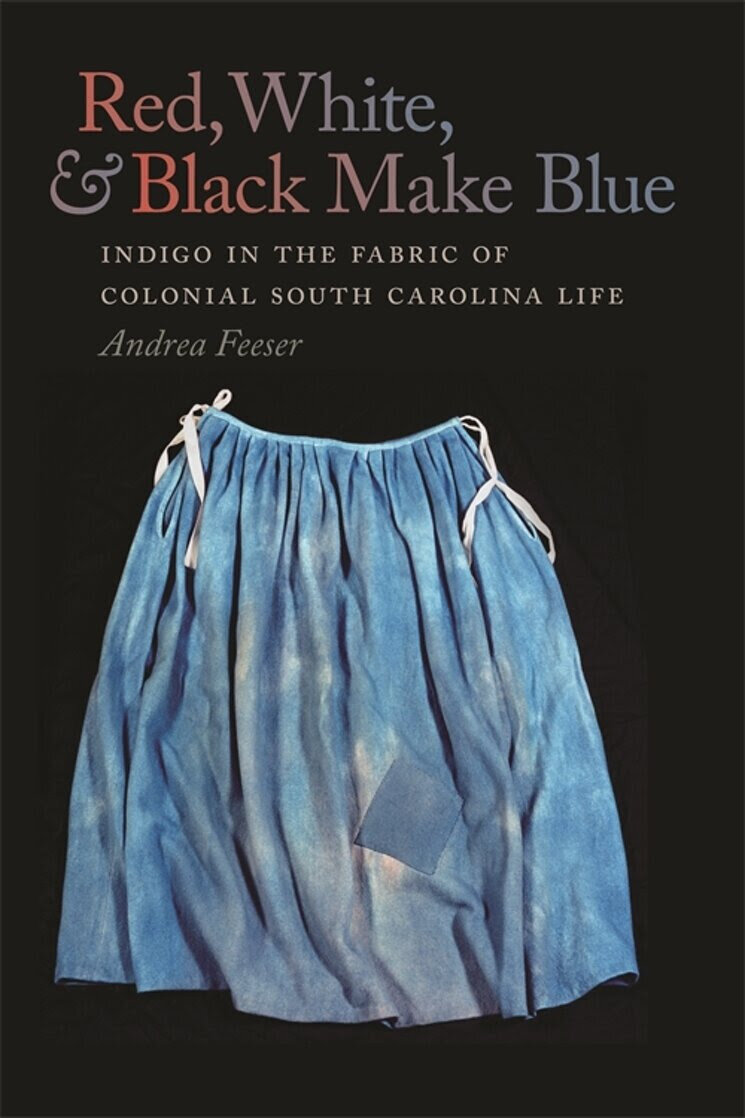

It's really important to acknowledge the history of indigo in the US. We can't just have stories of beautiful blue fibers without taking into account the realities of erasure, of stolen land, stolen people, stolen knowledge, stolen seeds. In the 1730s before cotton and rice became the main "cash crops" — indigofera suffruticosa was the most profitable export in the southern states. So much so that it was used as currency, blue gold. But the grave violence of this economic prosperity occurred through the kidnapping and forced enslavement of millions of African and Indigenous peoples. A couple of resources to dive deeper on this subject: Andrea Feeser’s book, Red White and Black Make Blue: Indigo in the Fabric of Colonial South is a good resource for learning more about this history. Michael A. Gomez’s reader, Diasporic Africa includes a chapter by Fredrick Knight about this history, entitled In An Ocean of Blue: West African Indigo Workers in the Atlantic World to 1800.

WPP: Does indigo have any soil-remediating properties? Is it healing to the land to grow indigo?

There are so many plant families with indigo-bearing properties, and each have their own unique characteristics. Fibershed has done a lot of research on climate beneficial indigo practices and provides generous opensource PDFs.

WPP: You were involved in an exciting project recently with Scott Sutton, aka Pigment Hunter: the Woad Warrior project. Can you tell me about what was involved? How did you & Scott meet?

I met Scott via Kara of Vibrant Valley Farm. Scott initiated the Woad Warriors with a few other local artisans to travel to the Siskiyou National Forest to investigate the invasive wild woad (isatis tinctoria). He contacted the Dept. of Noxious weeds and was given clear instructions on where to “Please, Yes, go harvest the woad,” as it’s something they are trying to eradicate. I have a whole new relationship to "invasive" plants and their classifications ... but that's a longer story for another day. We spent 3 days wild harvesting first and second year woad and trying various methods of fresh interaction and extraction. And we hope there is a Woad Warriors 2 adventure as we have learned much since our first visit, namely that we picked too early in the season and should have waited for the hot sunny weather. To be continued... you can witness our adventures and experiments in the "woad warriors 1" and "woad warriors 2" highlights on my Instagram account.

WPP: I’ve heard that there are MANY different plants that contain the molecule found in persica tinctoria responsible for dyeing. Can you remind me what that molecule is? How many different blue-dyeing plants have you worked with?

There are indeed hundreds of indigo-bearing plants which contain the precursor chemicals indican and isatin. I have worked directly with persicaria tinctoria & wild isatis tinctoria (woad) and with purchased extracted pigment from the indigofera tinctoria plant. A pal Rosa Chang has a beautiful project working on mapping out different plants geographically. (Editor’s note: It’s a really amazing project. Be sure to check it out, dear reader!).

WPP: I’m interested in how your work related to this wondrous plant, through Indigo Fest and the Natural Dye Podcast, has helped spread the popularity of indigo in your region. Can you tell me a little bit about the Festival and the Podcast? What are your goals/visions for both?

Collaboration is my favorite word and I have the privilege of working with some incredible people whom I admire so much. Kara Gilbert, Iris Sullivan Daire, the other brilliant cohort in Coastal Valley Blue pigment, and I hosted Indigofest '19 together at NorthFork 53 Farm. Iris and I partner in the evolution of Indigofest, which has been an annual celebration of local indigo and the culmination of the Northcoast Vat, entirely sourced with local ingredients, including pigment from our collective indigo plants. The vat is an offering to the community to share indigo, teach, learn, and encourage others to grow and build a relationship to the plant.

Last year's local vat contained native salal berries foraged near my home, locally grown overripe melon from a local farmer, and citrus peel pectin from a local juice shop as the reducing agent for the vat (it smelled amazing!). Our alkaline agent came from thermally decomposed oyster shell lime (from Williapa Bay oysters), which requires heating shells in a kiln over 1000° C to convert them from calcium carbonate to calcium oxide. We added water to produce our own calcium hydroxide! The vat was complete with rain water collected by Iris and Kara, and combined pigment from me and Iris. I can't properly express what it meant to dip local wool and angora gifted by local farms and friends into the local vat. Pure Magic! I encourage everyone to explore their own local vat possibilities. I explore some of these concepts in my upcoming online course offering, Intuitive Indigo Vatting, launching this fall on the Indigo Fest website.

Through my personal explorations of indigo, the Facebook group Indigo Pigment Extraction Methods was born and has evolved to a global community of incredible generous indigo growers and farmers. In this group, I host a live interview series called Blue Biographies, with a different indigo grower every Monday during the growing season. I am infinitely inspired and privileged to hold space for these stories. It has filled a personal deep need for me, for connection during this time of separation and honoring oral storytelling traditions.

I am also very overjoyed to assist Kelsey Doty in co-producing the Natural Dye Podcast, a new monthly podcast. We interview artists and discuss the broader range of natural dyes, not just indigo :)

Chalk pastels made with indigo blue pigment. Ground Bright subscribers this month can look forward to a recipe for making their own, included with their Coastal Valley Blue pigment. Photo by Christine James.

WPP: What physical property of indigo most thrills you? What’s the moment you love most in the cycle of your work with indigo?

I adore the process, more than the end result, always, every time. It's different, it challenges me, I feel the more I learn, the less, I know... and the less knowing matters, the deeper I fall into relationship and play with the plant. It is simultaneously the easiest dye to work with and the most complex. I will never tire of the magic of rubbing leaves together in my hand and watching the colors breath and stain my skin green-blue.

There is a good portion of the growing season in summer/fall that my hands are blue. I allow the fresh leaves or raw pigment to touch my hands but I do not stick them ungloved in the vat typically. This is not because of the indigo though, but because of the other ingredients that can be included in the numerous vat recipes. I try to encourage folks: if you do not very intimately have a relationship with every ingredient in your vat, then avoid putting ungloved hands in it. Particularly those with sensitive skin, who can experience skin irritation due to certain reducing agents like iron or the high alkaline environment due to lime. Your body is continually regulating its own PH. Introducing big PH game-changers via the largest organ in your body is something to be conscious of. If you build a local vat with intimately sourced ingredients, you may have a different experience, of your own volition. ;)

Indigo offers a generous range of colors, from sea foam blues and greens to pinks, purples, and every shade of sky blue to deep midnight sky almost black blue. The fermentation and reduction vats are most popular because not everyone has access to fresh plants or perhaps do not grow enough to produce many leaves. And I think also because the fresh processes respond to protein fibers in a more exciting way than with cellulose fibers. Vatting concentrated indigo pigment offers infinite shades of light to dark blue on all natural fibers. I am partial to fresh colors now as a grower but there's something for every mood. The fresh colors are light fast if applied properly to scoured cloth.

The plant has been used medicinally both topically and as tea for a long time. It has many medicinal properties, but is most known as anti-inflammatory. I enjoy the dried leaves as tea, I eat the bitter raw leaves occasionally, and I taste the leaf juice consistently during my fermentation process. I like to think think of it as a feedback loop for my literal and figurative gut instincts for determining the right timing for fermentation.

WPP: Would you recommend that anyone who’s interested try growing persica tinctoria? Is it easy to grow? What’s the minimum number of plants that one dyer could grow for a few baths of dye per year?

Yes, even just one plant can bring great joy but I recommend 10 to 20 plants if possible. It is a frost sensitive annual so it depends on your region. I start harvesting from approximately end of June until sometimes November here at the Oregon coast. I do know that persicaria tinctoria adapts in many climates as far north as Norway (in wind tunnels!) and far south as Brazil / Australia.

Photo by Christine James

Thank you, Britt! And, Iris and Kara too, for being such leaders of community sharing and building, and for your sweet sweet indigo contributions to this project.

Indigo is a plant with a powerful capacity to bring humans together. When the spirit of indigo, its soul, is ignored, brutal relationships — like those that formed in the early days of this nation — result. When the spirit of indigo is honored, it seems, it has the capacity to serve as a deep blue watering hole that unites and nourishes. As I package up these of envelopes of deep turquoise Coastal Valley Blue to send out to the community that supports Wild Pigment Project’s efforts to share closeness with the land and heal negative historical patterns, I do so with thanks, with reverence, and with curiosity about what new connections they’ll bring to each person who receives them.

Until Next Time,

Stay (in!) Tune[d] ~

<3 Tilke