pied midden: issue no 14 : deep listening: lorraine brigdale

Originally published September 4, 2020

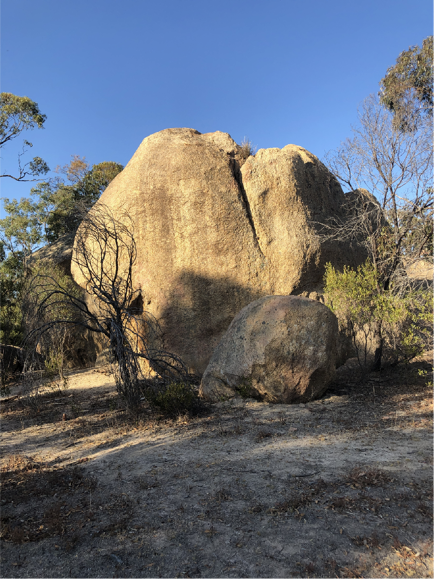

Land of the Jaara Jaara people of the DjaDja Warrung, Kooyoora State Park. Image courtesy of Lorraine Brigdale.

let’s talk

What does it mean for me to gather and make paint with the very body of the land whose people my ancestors treated with brutality and disrespect, and whom my culture of origin continues to disrespect and dishonor? When I first became interested in working with minerals and soils as pigments, I thought, perhaps I shouldn’t forage for earth pigments. How can I know what this means to the Kalapuyans, whose unceded land I live on?

I was originally motivated to work with earth pigments out of a desire to express my own personal, private, and yes, spiritual sense of intimacy with the land where I live, as well as a longing to align my art material use with my ecological values. But neither of those — genuine and well-intentioned — motivations addressed the question of whether it was culturally appropriate for me to use earth pigments. I did a lot of reading, and eventually, I learned that what I needed more than information was conversation. Conversation results from relationships with individuals, real people I meet and talk with, not just groups and organizations.

What I’ve learned from the conversations I’ve had so far is very specific to the places where I gather stones and plants, and is based on the cultural viewpoints of the people who talked with me. In a conversation with Esther Stutzman, a Kalapuya elder, storyteller and keeper of Kalapuya oral traditions, I learned that the pigments most relevant to Kalapuya culture, in her Yoncalla Kalapuya lineage, come from plants, because the primary materials used are woven from grasses and other plants. Ochres were likely also used as colorants, she says. But that knowledge has been lost to her as a result of the brutal attempts on the part of settler-colonizers to dismantle and destroy the Kalapuya people and culture through concentration-camp-style reservations and forced schooling.

I explained to Esther that I use the pigments I gather — mostly mineral, but some plants — in my own paintings, which explore intimacy with the land and the uncovering of cultural history. I also teach with the pigments, and of course, distribute some to Ground Bright subscribers. When I do, I donate the 22% to Esther Stutzman through the Kommema Cultural Protection Association, which funds research into Kalapuya culture, and a culture camp for youth.

Another thing I do is participate in a committee which cares for the Talking Stones, a series of boulders placed in a natural park area near my home, which are carved with words in the Kalapuya language. The stones are the result of a collaboration between a town committee and the Kalapuya community, and their placement lead to a significant event: the naming of the Whilamut Passage Bridge (a large bridge on the I5 corridor). ‘Whilamut’ means ‘where the river ripples and runs fast,’ and is a Kalapuya word that may be the source of the Willamette River’s name. It’s the first time that a Kalapuya word has been used by settler-colonizer culture to name a significant public infrastructure, which to the Kalapuya community is an acknowledgment and honoring of Kalapuya presence.

What my involvement in the Talking Stones committee looks like is regular attendance at what are sometimes tedious meetings, a lot of emailing, and a general commitment to understanding the sort bureaucratic language that I hate because as a synesthete who loves color, I find it hard to grasp what I think of as “gray” words — like ‘zoning,’ ‘intergovernmental agreement’ and ‘recreation district.’ I do it because the Talking Stones represent everything that feels right to me when I ask how I can give back to the land that gives to me: I’m tending to Kalapuya culture and helping share it with as many people as I can.

Pigments actually play an important role in helping care for the stones themselves. Occasionally, they get tagged with spray paint. Enough scrubbing gets the paint off, but also removes the stone’s delicate patina of lichen and age. When one of the members of the committee asked if I could use my water-based stone paints to recreate the patina, I was skeptical, thinking the rain would just wash them all away. I tried it, just to be polite, and to our delight, the paint held, almost seeming to be absorbed into the many tiny cracks in the rock’s basalt surface. This has left us with a technology for healing the stones, where none existed before.

Esther Stutzman felt that my use of pigments on Kalapuya lands, as I described it to her, was appropriate.

I received similar feedback from Northern Paiute elder Wilson Wewa Jr. A retelling of our conversation can be read in an earlier issue of Pied Midden. Wilson Wewa told me some things that have really helped guide me when working in Northern Paiute land in what’s also known as Eastern Oregon: only gather what you need for a specific project or use — don’t hoard. Mining for pigments is destructive and harmful to the land. Places of ceremony and sacred pictographs must be respected, honored and preserved forever. And, significantly, for me: if it feels good, it’s good. If it doesn’t feel good, it’s not good.

These conversations with elders weren’t ones I was able to have instantly, the second it occurred to me that it was a good idea to check in with local Indigenous elders before taking bagfuls of soil from stolen land to use in my art practice. Ok, that sounds more flip than I want it to. But. I’m just saying: working with the body of the land in a receptive way, with a desire to bring benefit to the land and respect its lineage of curators is an opportunity to develop relationships — an opportunity that would be lost if getting answers about the meaning of foraging on Native lands were as simple and easy as looking something up on the Interwebs. Relationships, and the acute listening that forms them are what will bring about the very healing and transformation that’s so needed.

Artists working with foraged pigments share history when we share pigments. With every stone we pick up, with every rock we crush, and each time we pass this practice along to others, we have a singular opportunity to champion land guardians and custodians, by acknowledging the cultural context of the pigments we work with. And a potent opportunity — and responsibility — to take action to protect land and support Indigenous communities through our work.

deep listening

Yorta Yorta artist and designer Lorraine Brigdale works within a tradition of what’s called ‘Gulpa Ngawal,’ which is Yorta Yorta for ‘deep listening.’ She paints with mineral earths and foraged pigments, some of which she gathers on her ancestral lands, after asking for permission from ancestors. She describes the development of her studio practice as growing alongside her process of learning more about her Yorta Yorta roots, and connecting with Yorta Yorta family. The two nourished each other, she explains.

With approval from Jaara Jaara elders, Lorraine gathered a beautiful sparkling mica on the land of the Jaara Jaara people of the DjaDja Warrung, to contribute to this month’s Ground Bright subscription. She’s named the mica Walwunmutj (the ‘j’ is pronounced like a ‘y’), which is the Yorta Yorta word for ‘shine.’ She’s directing September’s donation funds to Common Ground Australia, a First Nations-led organization which is dedicated to building a foundational level of knowledge for all Australians about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, through providing stories that will help bridge gaps in knowledge. It’s really an amazing group of writers and researchers — be sure to check it out.

Huge thanks to Lorraine and to DjaDja Warrung country for this generous contribution of a very special mineral which is more of a pigment enhancer than a pigment! Wulwunmutj can be used both to add sparkle to paint and to fired clay, as you’ll see.

In place of a standard interview, Lorraine has written this powerful account of her creative and family histories. An excerpt of this writing appears on her Pigment People page, on the Wild Pigment Project website.

gulpa ngawal, by lorraine brigdale:

To speak of my pigment work is to speak of my ancestors, my heart, my family, my people, my country.

An integral part of my art practice involves ‘Gulpa Ngawal,’ or Deep Listening, in Yorta Yorta language. Deep Listening is a concept that is a widespread culture in Indigenous Nations across Australia. It is not about our ears, its about our attention. There are many words describing this state of Deep Listening and I believe that it is at the core of Aboriginal spirituality.

Words for Deep Listening in a few different Aboriginal languages:

Gulpa NgawalIn (in Yorta Yorta language of Victoria): a deep and respectful listening which builds community.

Nyernila (in DjaDjaWurrung language of the Jarra people) : to hear, listen, understand, know, answer through deep listening.

Dadirri (in Ngungikurungkurr language in the Northern Territory) : to hear, listen, understand, know, answer through deep listening.

"In the Ngungikurungkurr language of the Daly River in the Northern Territory, the word for "Deep Listening" is 'Dadirri' (Ungunmurr, 2009) and in the Yorta Yorta language of the Murray River in Victoria, it is 'Gulpa Ngawal'. The closest we can get to describing it in English is deep and respectful listening which builds community. Deep listening draws on many senses beyond what is simply heard. It can take place in silence. Deep listening can be applied as a way of being together, as a research methodology and as a way of making a difference.”

~ From Selected bibliography of material from Gulpa ngawal : Indigenous deep listening by Laura Brearley

But feeling this connection to country is not something that every Aboriginal person automatically has in their life, due to colonization and its results over the past 200 years. Once this connection is again seeded it does grow and for many Aboriginal people, a recognition of that connection and reciprocity (caring for country), brings a feeling of belonging that they may not have felt before. Many describe previously feeling an emotional black hole that is now starting to be filled, or feeling whole for the first time. We start to find that superficial things have little meaning when what really matters is the health of our people, our land, our country, our unique animals, our plants and trees, the earth. We start to accept responsibility for our actions and our waste. This knowledge comes to us through connecting with community and country and through Gulpa NgawalIn - deep listening, which is really learning to listen to country and ancestral memory.

I’m a proud Yorta Yorta woman, daughter, mother and artist. My Aboriginal family on the maternal side originates from the Ulupna Clan in the Barmah Forest on the border of NSW and Victoria.

My creative journey and understanding of my Aboriginal family is undeniably linked. Learning and developing my ochre explorations alongside an ever-growing knowledge about my Aboriginal family brings me joy, sadness and a real feeling of belonging at last.

Ceramic Object by Lorraine Brigdale. Image courtesy of Lorraine Brigdale.

My grandmother was born and grown up on Country at Cumeragunga Aboriginal Mission in Victoria. When she wanted to marry my white grandfather, who was already father to two of her children, she had to apply to the government for permission to marry, and also apply for a Certificate of Exemption to be allowed to live with her husband. She had no choice. Her husband was her and her children’s future, and staying alone on the mission would put have put her children in danger of being taken by the authorities.

The Certificate of Exemption prohibited her from having contact with any Aboriginal people, especially her family. She left her country with her husband and never saw her family again. She lived most of her adult life having no contact or support from her Yorta Yorta family. She never went back to her country. This meant that my mother knew nothing of her ancestry and in turn neither did I. In recent years we've come to learn many parts of my Nan’s story. There is so much we will never know — it’s a difficult sad, journey, not one that we come equipped for. But with knowledge comes power and in the case of my Indigenous ancestors this is true. As the black hole fills and I dig my hands deeper into the ochre, I gain strength and sense of belonging I never imagined. My family story is a part of a contemporary Australian conversation about family, place and connection which is never far from my heart. Working with Ochre restores me to this history and to my heart.

As an artist, my creative life has always included learning, teaching, and sharing my art practices, my culture and love of country. Making art from natural and found materials is a creative urge which is in my blood, and comes from my ancestral memory. It’s my country’s way of calling me home.

The widespread cultural use of ochre and charcoal in paintings and rock art to record events and stories by Australian Aboriginals over many many thousands of years has been well documented. Ochre has been used since the beginning of aboriginal life on this country for storytelling, logging of memories, decoration of tools and weapons, and also for body markings in spiritual ceremonies, auspicious occasions and hunting.

My artistic response to the landscape, in the form of painting with ochres, led me to create natural paintings that tell the story of my art and personal journeys. I’ve further developed my ochre painting, taking my Indigenous heritage and moving with it into my contemporary life and art works. I fossick (forage) for rocks in and around Victoria. I’ve also been gifted pieces by my Uncle’s ochre collection, from my sisters who learn from me what to source, as well as from other generous Aboriginal Artists as gifts from their country.

Ceramic Objects by Lorraine Brigdale. Image courtesy of Lorraine Brigdale.

There is something mystical about preparing ochre, handling it and ultimately painting with it. A sense of peace and timelessness descends, but it’s more than this. It’s about deep listening. Connecting with the earth brings me in touch with beings and organic life from the evolution of time, and it connects me to my ancestors and to all people. Iron-rich ochre containing oxygen connects me to the people and country we come from. There is ochre at the heart. I’m using the materials from my land, in my own way, telling my story. Ochre links me intimately with my origins. The ground we walk on, innate in its beauty is often overlooked as people search for what is beyond and beckoning. I look down at what is often missed underfoot, to the rhythm of nature herself, capturing my country’s story in minute detail. Nature shares its resources with me, then I create.

My art works are created with hand ground ochres and minerals, using Australian Acacia Gum resin as a binder. I work with natural, hand-sourced and prepared materials. Having my hands in dirt and pigment that is hundreds of thousands of years in the making connects me directly to Ancestors. Creating art with these natural materials also allows for a more sustainable practice. Ancestors have shown me to use ochre and charcoal together with gum resin in this way.

I’m led by a creative urge to create more contemporary forms, images & ideas, using traditional materials. The earth interests me, the colours, the textures, the energy. I look steadily, intently with great curiosity, interest & pleasure. I’ve been an artist all my life, from my early days making pictures in the dirt and the sand, through the ups and downs of being a potter and paint artist. I love to have my hands in clay, been playing in mud all my life. Using stones and earth intrigues and inspires me. I know it’s in my DNA, working with ochre & minerals. I learn to understand what it says to me and how it behaves in a contemporary exploration of an age-old medium.

Kooyoora Paintings by Lorraine Brigdale. Image courtesy of Lorraine Brigdale.

My working life has taken me to many countries and this time of travel gifted me opportunities to embed with other cultures, explore, listen, learn and create. Working as a Designer most of my professional life, I spent 5 years in India and Asia, which provided new insights into people, culture and history and the influence of geography on humankind. In the process my understanding of self and self in relation to place grew, as did my thirst for knowledge of my own Indigenous ancestors, their lives, skills and traditions.

On returning to Australia I was influenced by these new insights and became driven to immerse my creative self, returning once again to exploring ochres, developing my knowledge of this precious traditional resource, making pigments from these stones, and making paint to my paint with. I was led by my cultural and ancestral memory, while simultaneously exploring how ochres, combined with other minerals, work as a contemporary art medium. Following my artistic response to local landscape, environment and history in the form of painting with ochres and minerals gave birth to my further paint-making studies. I wanted to paint things with my natural ochres that were truly linked with the natural state of the minerals. Simply put, I wanted to paint and make paint. I had started a new love affair. Since, I’ve experimented with making paint from ochres and minerals, and inks from plant matter. While I developed these paints and inks first and foremost for making my own artwork, I am now working toward releasing my natural paint range, Iyoga Woka (Iyoga is pronounced E-or-ga) This means Stone Country. Iyoga is the Yorta Yorta word for ‘Stone,’ and Woka is the Yorta Yorta word for ‘Earth/Ground/Country/District.’

I am a proud Yorta Yorta woman and have always been experimental with my art, and it reflects me as an Indigenous woman. The fact that I’m learning about my inherited culture at this stage in my life is a result of the effect on my family of the period called “stolen generations” and the time of colonial rule over my people and my land. My personal Indigenous inheritance shows me the way to create from the land and understand my own and my ancestors stories. Trauma goes back 5 generations, but going forward with the help of the earth, I’m working to help my descendants understand and accept better how to be strong Yorta Yorta people in our way.

~ Lorraine Brigdale, August 2020

Thank you, Lorraine, for all you’ve shared!

To receive this sparkly golden Walwunmutj in your mailbox this month, you still have time to subscribe to Ground Bright (until…midnight on September 11th, Oregon Time, to be precise!).

mail room

I’ve been getting some really lovely mail lately. Like the letter and sweet little color sample painting pictured below, the contents of which had me floating on a cloud. Mail is in fact one of the few ways we can connect tangibly with people who don’t live in our household in these strange times. I thought of that this week as I carefully spooned Lorraine’s Walwunmutj mica into little bags, and painted the end of each Ground Bright tag with the radiant dust.

I remembered my bare feet, age four, moving over the ground under Eucalyptus trees a couple hours south of Kooyoora State park, at my grandparent’s house — the haunting camphor smell of the trees and the power of that place, how it filled me as a child.

I thought of Lorraine walking on Jaara Jaara land, also breathing that gum tree air, and practicing Gulpa Ngawal, and picking up the large chunk of mica rock that became the Walwunmutj, grinding it, washing it, levigating it, and wrapping it all up to mail to me.

And now, I’m thinking of all the hands that will touch these brown envelopes I mail out, all the fingers that will dip with delight into the scintillations within and be raised to the light for maximum wow.

We’re touching.

Fan mail!! This really made my week. :)

I also treasure the emails I’m often fortunate to receive after I press ‘send’ on these newsletter. Last month, after the issue about Coastal Valley blue, I got this one in my Inbox:

Hello, Friend,

Just wanted to let you know that everything about this newsletter filled me with such joy and happiness and brought me to tears. It is so sincere, filled with beautiful news, beautiful images, and beautiful sentiment and had such a pure honesty about it. I’m very new to the pigment world and am slowly dipping my toe into it but feel a strong pull toward it deep within my cells. I have had the absolute privilege to begin my learning with Heidi Gustafson in her magical studio in WA. I recently created space in my studio and dedicated it to pigment work. I’m not sure where this will take me, I have no plans or goals or objects other than to enjoy the whole experience.

All this is to say, you are bright light on my pigment journey and I value your voice so much.

Cheers,

Barb Skoog

Words fail me a little here, Barb! Thank you sooo much for your bountiful encouragement, and for this window into your own pigment practice.

That’s all for now!

Until Next Time,

Stay In Touch

<3 Tilke